Written by Louise Cowan, Trainee Liaison Librarian

This week’s Travel Thursday follows the voyages of the ship Alceste as recounted by the ship’s surgeon,

Captain Maxwell

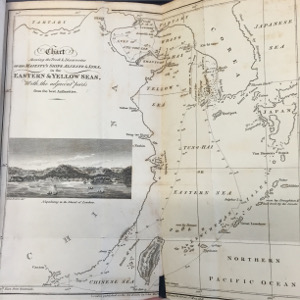

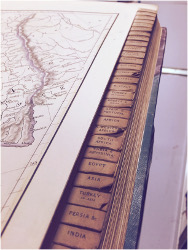

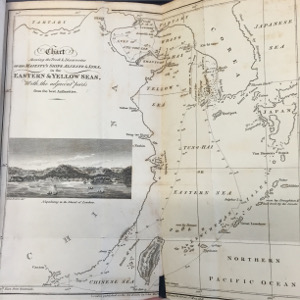

John McLeod in his ‘Voyage of His Majesty’s Ship Alceste to China, Corea, and the Island of Lewchew with an account of her shipwreck’ (3rd ed, 1820) [Reserve 915.1]. Under the command of Captain Murray Maxwell, the Alceste was one of the first British vessels to visit Okinawa Island (Lewchew), the largest of the Ryukyu Islands of Japan.

The purpose of the voyage was to transport Ambassador, Lord Amherst to the court of the Chinese Emperor at Peking, in an attempt to open trade with China. The Alceste sailed in 1816, travelling via Rio de Janeiro and the Cape of Good Hope to China. Once the Ambassador and his delegation had disembarked, the Captain and crew continued on to explore the region.

Unfortunately, their visits were not always welcomed by the local people, particularly off the West coast of Korea: “The natives here exhibited, by signs and gestures, the greatest aversion to the landing of a party of ships, making cut throat motions by drawing their

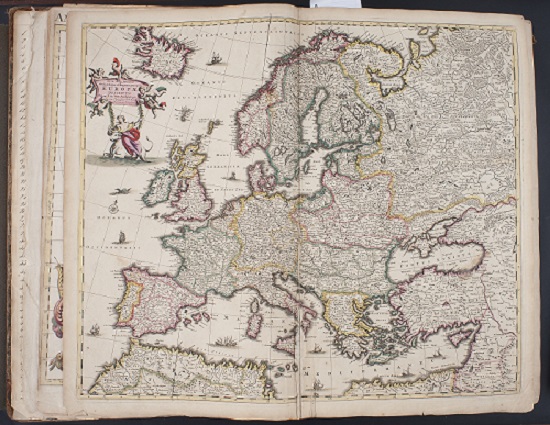

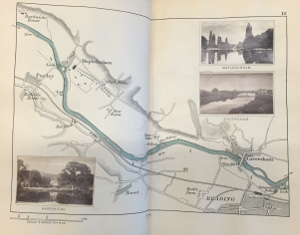

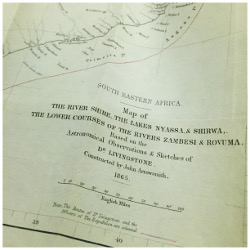

Chart showing the track and discoveries of the Alceste

hands across their necks and pushing the boats away from the beach.”

It seems as though the Korean people had been forbidden from welcoming strangers to their shores, for when the crew did make land, a chief they had befriended at sea,”clasped his hands in mournful silence; at last bursting into a fit of crying” then seemed to “intimate that in four days […] he should lose his head’’ and refused to welcome them beyond the beach.

They had a more friendly reception on the Island of Lewchew (Okinawa) where, after a cautious introduction, some officers were invited ashore and hospitably entertained, “Many loyal and friendly toasts, applicable to both countries were given and drank with enthusiasm.”

The crew spent several months with the island people, learning about their language, customs and traditions. McLeod reports for example on the nature of their dance: “The mode of dancing of these people may, strictly speaking, be termed hopping” but the crew did their best to join in forming “a grotesque assembly”.

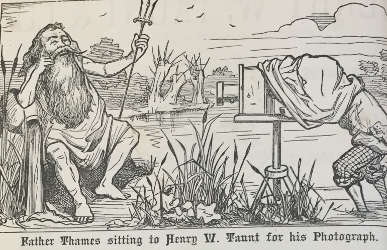

‘Lewchewan’ Chief

The surgeon also reports on the medical practices of the islanders, noting that when Captain Maxwell injured his finger, the island people were keen to help, sending for one of their surgical professors…“The injury having being examined […] a fowl was killed with much form, and skinned, and a composition of flour and eggs, with some warm ingredients about the consistence of dough, was put around the fractured part, (Which had the effect of retaining it in its position) and the whole enclosed in the skin of the fowl.”

One of the happiest occasions occurred on 25th October when the people came together to celebrate the anniversary of the coronation of George III. The islanders, “sent on board the ship a great number of coloured paper lanterns, for the purpose of illuminating her at night, in honour of our King.” McLeod states that the day was so remarkable that it would, “often be recalled with delight by all who witnessed the pleasing scene of two people […] harmoniously united in hearty good will and convivial friendship.”

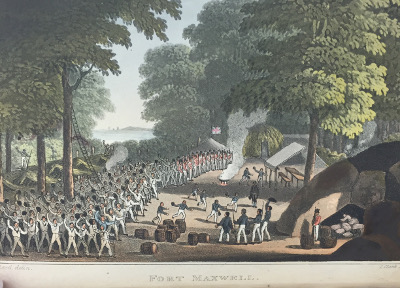

Shortly after, the Alceste left the island and returned to China to collect Lord Amherst, whose delegation had been an unfortunate failure. From there, the crew’s return journey was fraught with a number of difficulties; not only were they shipwrecked and

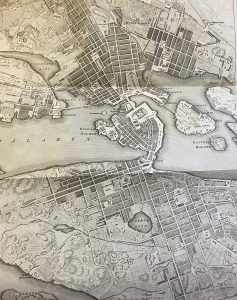

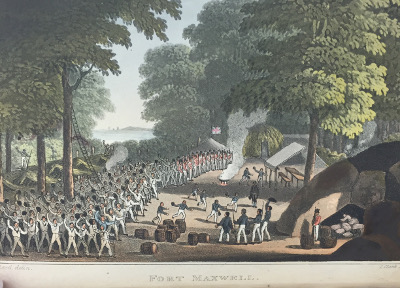

Fort Maxwell – the fort built after the Alceste was shipwrecked, named for her captain.

attacked by ferocious Malay pirates but their rescue ship, the Caesar, also caught fire!

The voyage home further saw the arrival of two interesting passengers when they made port at Batavia, “a snake of that species called Boa Constrictor; the other an Ourang-Outang.” McLeod recounts the occasion of them feeding the snake a goat with great fascination, explaining that, “the whole operation of completely gorging the goat occupied about two hours and twenty minutes.” The ship’s officers also encountered Napoleon Buonaparte at St Helen’s. Of the French military officer, McLeod states: “Whatever may be his general habit, he can behave himself very prettily if he pleases.”

The crew finally reached home in the autumn of 1817 after a journey of twenty months (Beijing Center). McLeod published his account of the voyage shortly after his return; a popular work, second and third editions were later released in 1819 and 1820 respectively, (Beijing Center).

Sources:

Beijing Center – Voyage of His Majesty’s Ship Alceste

Office of the Historian – Lew Chew

Naval Military Press