Wright, and Wright (c.1909) The Vegetable Grower’s Guide.

Written by Louise Cowan, Trainee Liaison Librarian

It is not uncommon for inexperienced people to be guilty of omissions in providing for the establishment of a garden which strike horticulturists as almost ludicrous.

(Wright and Wright, 1909)

In honour of National Allotment Week we have dug up some handy horticultural tips from our collections to help turn us all into green-fingered gardeners!

Let’s start with some basics:

Tip #1: Setting out your plot the right way can make a big difference:

“All kitchen garden students should be taught the simple rule of arranging their plots so that the rows of vegetables run north and south. This permits of sun rays getting free access to the rows. When they run east to west the sun is kept from the inner rows by the outer ones in the case of tall crops.” (Wright and Wright, 1909)

Wright and Wright (1909) also suggest that a parallelogram shaped plot is best and emphasise not to forget planning in space for paths when designing your allotment garden!

Gardening Tools (Wright and Wright, 1909)

Tip #2: Always have the right equipment for the job!

“Garden equipment cannot be provided without expense, and it is wise to face what is entailed resolutely.” (Wright and Wright, 1909)

There certainly is a lot to consider but this helpful illustration (right) should help you know your dibble from your bill-hook!

Tip #3: Make sure your plants get enough water at the right time:

When it comes to watering plants, Moore (1881) cautions that, “it is a wrong though common practice to press the surface of the soil in the pot in order to feel if it is moist enough, this soon consolidates it, and prevents it from getting the full benefit of aeration.”

While Garton (1769) helpfully adds, “whilst the nights are frosty water your plants in the morning; in warm weather water than in the evening, before the sun goes down.”

Now we have the hang of the fundamentals, how do we go about growing some vegetables?

Carrots (Wright and Wright, 1909)

Tip #4: Getting the soil right is very important!

According to Moore (1881) the enrichment of soil is often overlooked so when planting onions for example, remember, “a portion of good soil should be provided for each plant, and heavy mulchings of manure should be placed upon the surface as soon as practical after planting to prevent the soil becoming dry and parched.”

While for carrots, Wright and Wright (1909) suggest that, “the land best suited […] is unquestionably a deep, sandy loam. […] They are best grown after celery or some other fibrous-rooted crop for which the ground was manured the previous year.”

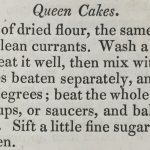

Tip #5: Not any old carrot will do, make sure yours are the cream of the crop with this advice from Wright and Wright (1909):

“Thinning is of the first importance, as on it turns not only the question of getting shapely roots, but also of baffling the maggot. […] Carrots should always be thinned twice; the first time a few days after they have come through, the second when they are about the size of radishes.”

To make sure your carrots are a rich bright red, try mixing soot and wood ashes “into the drills when the seed is sown.” (Wright and Wright, 1909)

Tip #6: Protect your plants and keep garden enemies at bay:

To fight against an attack by slugs and snails, Wright and Wright (1909) suggest that as, “they are principally night feeders, […] an attack can be stopped by looking over the beds at night with the aid of a lantern, dropping any slugs into a jar of brine. Lime dusted round the outsides of the bed will stop the approach of fresh hordes.”

Onions (Wright and Wright, 1909)

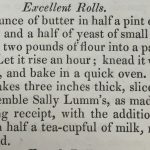

Tip #7: Harvest your crops with care:

You have chosen the right soil, fought off the slugs, tended your plants with care and it’s finally time to reap your rewards but while some vegetables can be easily pulled up Wright and Wright (1909) suggest a different method for large onions:

“The authors find it a good plan to gently heave the best bulbs from side to side with the hands day after day for a week, breaking a few roots each time, and thus bringing growth to a standstill by degrees. This answers much better than forking them straight out of the ground at one operation.”

Great advice, now what should we be doing in our allotments during August?

In his, ‘The Practical Gardener and Gentleman’s Directory, for Every Month in the Year,’ Garton (1769) makes some useful suggestions:

- “Cauliflower-seed to produce an early crop next summer must be sown between the 18th and 24th of this month, which will be ready to plant under frames in the last week in October, to remain there till the latter end of February, or beginning of March.”

- “Weed and keep clean the asparagus beds, and the plants sown in the spring. Do this work with the hand only.”

- “Sow carrots for spring use. Do this in the 3rd or 4th week of this month, and don’t sow this seed too thick.”

- “This being the season for pickling cucumbers; they must be well watered in dry weather, three or four times a week; and be gathered at proper sizes three times a week.”

Finally, according to Mrs Loudon (1870), August is “about the best time of the year to visit famous gardens, one of the best ways of improving our knowledge of the art of gardening.”

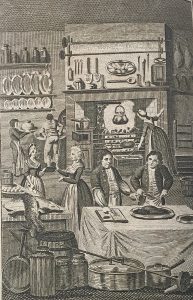

![Frontpieve from 'The Complete Gardener' by Thomas Mawe and John Abercrombie, 1854 [MERL LIBRARY RESERVE--4756-MAW]](https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2016/08/frontpiece-garden.jpg)

Frontpieve from ‘The Complete Gardener’ by Thomas Mawe and John Abercrombie, 1854 [MERL LIBRARY RESERVE–4756-MAW]

You can find more advice on allotments and growing your own food at the National Allotment Society webpage.

Sources:

Moore, Thomas (1881) Epitome of Gardening. Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black [MERL LIBRARY RESERVE–4756-MOO]

Wright, J. and Wright, H. J. (c.1909) The Vegetable Grower’s Guide. London: Virtue and Co. [MERL LIBRARY RESERVE–4752-WRI]

Garton, James (1769) The Practical Gardener and Gentleman’s Directory, for Every Month in the Year. London: E and C Dilly [RESERVE– ]

Mrs Loudon (1870) The Amateur Gardener’s Calendar. London: Frederick Warne and Co. [RESERVE–635-LOU]

All items are available upon request.

![Frontpieve from 'The Complete Gardener' by Thomas Mawe and John Abercrombie, 1854 [MERL LIBRARY RESERVE--4756-MAW]](https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2016/08/frontpiece-garden.jpg)

![Tabby Polka [Spellman Collection]](https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2016/06/tabby-polka-230x300.jpg)

![gif of cat anatomy from Anatomie descriptive et comparative du chat by Hercule Straus-Durckheim, 1845. [Cole Large 09]](https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/special-collections/files/2016/06/catAT3.gif)