This post comes from Brian Ryder, one of our volunteers here at Special Collections. Brian’s history with Reading collections is a long one; he used to be one of our project cataloguers and is now working his way through the Routledge & Kegan Paul archive.

In 1948, Philip Unwin of publishers George Allen & Unwin went on holiday with his family to Norway and broke the ‘tedium’ of endless days of leisure by pleasing his hyperactive uncle and boss Stanley Unwin, the firm’s founder, by visiting Oslo’s leading publisher. A result of this initiative was the offer of first refusal for English language rights in The Kon-Tiki Expedition by Thor Heyerdahl – the story of six men, led by the author, who constructed a raft from balsa trunks and sailed for 100 days and 6,000 kilometres from Peru to the Polynesian islands. The object of this exercise was to test Heyerdahl’s theory that in pre-Columbian times it was South American Indians who had first populated these islands.

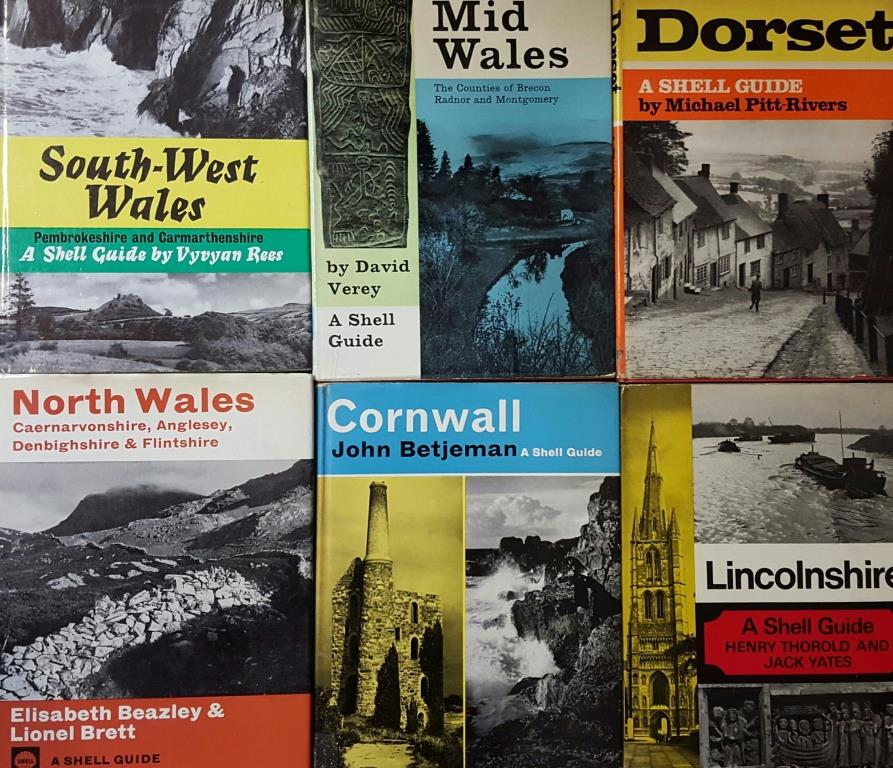

A colourised photo of Kon-Tiki

The English translation, by F.H. Lyon, was completed in the summer of 1949 and the book was published on 31 March 1950. Heyerdahl wrote, and spoke, excellent English and threw himself into a punishing series of events to launch the book in London. He was helped in this task by having a film to show about the expedition – a compilation of footage taken on the journey – which the following year won an Oscar for best documentary. No publisher had been found for the book in the United States but the availability of their English translation enabled Allen & Unwin to secure one. Translations into other languages also appeared around the world, several of them made from Lyon’s English edition rather than from the original Norwegian.

The book became a bestseller; the first Allen & Unwin had ever had during their thirty-five year existence. In this it had a pace-maker in the equally successful The Wooden Horse by Eric Williams, a World War II escape story, published a few months earlier by Collins; both claimed worldwide sales of a million copies at about the same time. Stanley Unwin was generous with the immense profits made by the book, giving a Christmas bonus to everyone inside the firm and to all those outside it, like F.H. Lyon, who had played a part in the book’s success. He also set up a company pension scheme although, just as there had been only one bestseller in the firm’s first thirty-five years, there had only been one employee to have retired – this being the company secretary Spencer Stallybrass, and he waited until he was eighty to do so.

Two other members of Kon-Tiki’s crew also became authors and were published by Allen & Unwin. Erik Hesselberg, the team’s navigator and artist, illustrated his own amusing account of the expedition and Bengt Danielsson, like Heyerdahl an anthropologist, wrote several successful books including The Happy Island about Raroia, upon which Kon-Tiki had beached at the end of its voyage. Other Norwegian authors, noting what Allen & Unwin had done for their literary compatriots, offered them their works. All in all Philip Unwin’s holiday in Norway had resulted in his uncle’s firm joining the big league of British publishers.

Authors’ correspondence with their publishers rarely concerns more than routine matters of production and publicity, but Heyerdahl and Philip Unwin became firm friends and some of Thor’s letters contain interesting and amusing reports of his life. On one occasion in 1953 Heyerdahl was among two hundred guests at the British Embassy in Oslo for a ‘gala with ball’ at which Princess Margaret was the guest of honour. The ambassador and his wife, along with Heyerdahl and the Princess, dined separately; ‘with much champagne and nobody to disturb us, we got very friendly and had a lot of fun. THEN it happened!’ It turned out that Heyerdahl was to open the dancing by partnering the Princess. While he protested that he had never danced anything, apart from the hula-hula and Indian war dances during his travels around the world, the band struck up with a samba and the Princess said, ‘If you do not want to dance samba with me, then I shall have to dance hula with you!’ ‘By then I was left with no choice, everybody there waiting for us to get going, I closed my eyes and pushed the Princess onto the big open floor and jumped around in what according to the music was supposed to be a samba!’

At the end of what Thor described as her very well-received visit to Norway the Princess returned to London for her sister’s coronation. On the day after that she wrote to Heyerdahl and told him she still did not believe that he did not dance while Philip Unwin reported to him that the British popular papers were full ‘of your prowess on the dance floor’ in their accounts of the ball at the embassy.

During his lifetime Heyerdahl did not give up on his theory about the origins of the first settlers on the Polynesian Islands but nor was it generally accepted. However, in 2011 DNA testing did reveal that genetic links could be made between today’s islanders and South Americans while a Norwegian feature film simply entitled Kon-Tiki was nominated for both Academy and Golden Globe awards in 2012. Heyerdahl and his expedition are not forgotten.

–Brian Ryder, in memory of David and Periwinkle Unwin, good friends of the archive. David Unwin (1918-2010) was the elder son of publisher Sir Stanley Unwin and became a successful children’s author under the pseudonym David Severn. From childhood he had always appeared to be in poor health but after his marriage to Periwinkle, a niece of the author A.P. Herbert, his health greatly improved and he outlived his apparently more robust and younger siblings. He did not spend much of his working life directly employed by the firm but they did make use of his photographic and typographic skills and also his many enthusiasms including those for art, film, horticulture and the countryside in which fields he was often asked to supply reader’s reports. After his brother Rayner, then in charge of Allen & Unwin, deposited its archive with the University David and Periwinkle paid visits to see how it was housed and what gems I, the cataloguer, had found. Later, they occasionally invited me to visit them for lunch after which I usually found myself returning with donations of books and other items relevant to the Unwin publishing and family collections. After David died Periwinkle deposited his publishing correspondence with us along with volumes from his library which were of value to our children’s literature collection. Sadly she died just before Christmas 2014.