Following the 200th anniversary of Queen Victoria’s birth, Liaison Librarian Bethan Davies takes a closer look at our Special Collections and the surprising connections with the famous monarch.

Housed in the red brick building designed by Alfred Waterhouse for Alfred Palmer, it is hard not to see the connection between the Victorians and Special Collections. Our Children’s Collection is particularly strong in 19th Century titles, and many of our business archives cover the Victorian period (including Huntley & Palmers, De La Rue, Chatto & Windus). We hold an entire collection focused on The Great Exhibition of 1851, patronised by Prince Albert, and the Spellman Collection focuses entirely on Victorian piano hall music covers. Several of our archives hold documents on Victorian illustrators and authors including Audrey Beardsley, Pearl Craigie, and Violet Fane.

Therefore, it is not surprising that Queen Victoria herself makes appearances throughout our Collections, especially around moments of change and commemoration. The breadth and age of our Collections also allow us to view Victoria throughout history, and chart the various changes throughout her life.

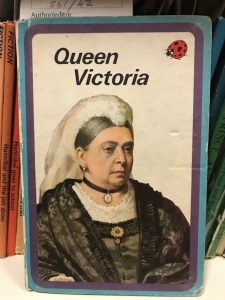

Queen Victoria (1976), part of our Ladybird Collection

Changing Faces

When we think of Victoria, we often think of the image we see on the cover of the 1976 Ladybird title Queen Victoria (see above). This depiction is from Victoria’s later years. However, we can see images of Victoria’s youth from the children’s book The Queen’s resolve : “I will be good” and her “doubly royal” reign (1897), written by Charles Bullock. The front cover depicts two oval images of Victoria facing each other, one a child, the other the elder Queen (see below). Bullock notes in his title that whilst the book is intended for younger readers, it might also be of interest to “Old England,” looking back to the beginning of the Queen’s reign and the “boundless enthusiasm” which accompanied her coronation. The title refers to a popular story that upon discovering that she was heir to the throne, Victoria exclaimed, “I will be good!” Written in commemoration of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, Bullock not only celebrates her rule, but her role as a mother and wife, which he calls her “double rule”.

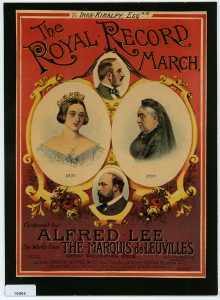

The Spellman Collection, which offers fascinating depictions of Victoria throughout her reign, is equally interested in both Victoria’s personal life. A key example of this can be seen in The Royal Record March (1897), composed by Alfred Lee, and the notorious Marquis de Leuvilles in celebration of Victoria’s Silver Jubilee. Similar to The Queen’s Resolve, two images (one younger, one older) of Victoria face each other, although the younger Victoria is shown just before she took the throne. The cover also depicts her husband, the late Prince Albert, explicitly denoting his continuing importance in her life, even after his death.

- The Queen’s Resolve (1897) by Charles Bullock.

- The Royal Record March (1897), unknown artist, Spellman Collection.

Coronation and Childhood

The “boundless enthusiasm” noted by Bullock regarding the Queen’s coronation in 1838, can be seen in a rare special edition of The Sun held in our Printing Collection (not connected to the modern newspaper of the same name). Created with the “special exertion of M. De La Rue”, the edition is noted for using gold ink rather than black, and includes a poem to mark the occasion created by the editor Murdo Young. Through both items, the general excitement of a new monarch can be felt, alongside the youth of the new Queen, who was then only 18 years old. Young’s “Sketch” of the new Queen makes note of her childhood, future reforms which needed to be made to the monarchy, and in particular her short stature.

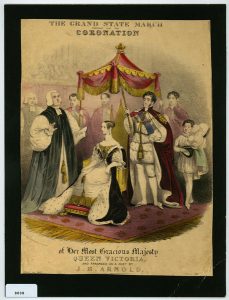

The coronation was also commemorated by composer J.B. Arnold with The Grand state march: composed for the coronation of her most gracious majesty Queen Victoria (1837). Our copy from the Spellman Collection depicts an image of the young Queen on the front cover, enthroned and about to be crowned.

- The Sun, Special edition to commemorate the coronation of Queen Victoria (PRINTING COLLECTION LARGE–072)

- The Grand State March (1937), artist unknown, Spellman Collection.

Change and Exhibition

The image of the younger Victoria is also present in the Stenton Coin Collection. Although the collection focuses on coins from the Anglo-Saxon and Norman period, it also includes this 1839 copper halfpenny, from the Isle of Man. At the time, the Isle of Man had separate coinage issued compared to the rest of the country. This was overturned in the Act of 1839, which aligned the Isle of Man with the United Kingdom’s currency. The 1839 coinage, updated to include Victoria’s face, was the last update to the Isle of Man’s currency, until the introduction of decimal coinage in 1971.

One of the most well-known examples of Victoria’s legacy was in the creation of the Great Exhibition of 1851, housed in the Crystal Palace. The moment was commemorated by the lithographers the Leighton Brothers, with The Queen’s March (1851). Now part of our Great Exhibition Collection, this stately march shows the Queen, alongside Prince Albert, who was the patron of the Great Exhibition. Our Collection includes the official Catalogue and reports on the Great Exhibition and its influence upon the British Society, alongside ephemera and souvenirs!

- Victorian 1839 copper halfpenny (501*) from the Stenton Coin Collection.

- The Queen’s state march (1851), Leighton Brothers. Now housed in the Great Exhibition Collection (GREAT EXHIBITION BOX–01/22)

This is only a glimpse into all our holdings on Queen Victoria. Click the links to find out more about our Collections! Want more information? Contact Special Collections at specialcollections@reading.ac.uk.