Checking though the list of Whiteknights Campus plants (compiled by David Grice, a recent Reading botany undergraduate) I came across references to no fewer than seven willow herb species, two of which have caused me considerable confusion, square-stemmed willow-herb (Epilobium tetragonum) and short-fruited willow-herb (Epilobium obscurum). Willow-herbs are of course those weedy plants (family Onagraceae) recognised by their opposite leaves, pink flowers and long seed capsule releasing numerous seeds with their fluffy appendages which blow all over the shop in summer. Easy to ignore these plants as ‘just weeds’ but there are fourteen species listed by Stace in the 3rd edition of his standard flora and it can be difficult to distinguish between some of them – like the two mentioned above. Stace says that seed-coat ornamentation is highly diagnostic but this is no help in early spring when seeds, let alone their ornamented coats, are months away! Even with flowers E.tetragonum and E.obscurum can look remarkably similar; both about the same height and growth form, with pale purplish pink flowers and both grow often together in the same habitats – hedgerows, open woods, cultivated and waste ground. And it was in just such a piece of waste ground in the Harris Garden that I found the two species growing side by side pictured above in situ and below on the botanist’s slab.

-

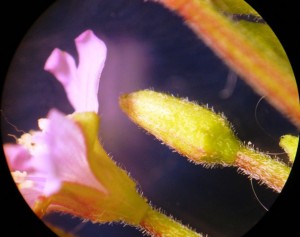

Of course as with all plants there ARE some clear differences and once you get your eye in the two initially similar plants have their own personalities. Flowering specimens are relatively easily distinguished by the nature of the hairs on their floral parts; E.obscurum has glandular hairs while E.tetragonum has appressed hairs only. On a nice sunny day if we take the plant and ‘htl’ (hold to light) we can see the glistening glandular hairs of E.obscurum and make the distinction with the appressed hairy but non-glandular E.tetragonum with some satisfaction.

But roll back a few months, when flowers, fruits and their hairs, glandular or otherwise, are not in evidence, what do we do then to distinguish between these two? Well, for non-flowering specimens of these and all other species in the British flora we are lucky to have the recently published vegetative key by Poland & Clement, a most valuable addition to the British botanists’ toolkit. So, turning to page 433 in the section appropriately titled ‘EPIL’ I find a detailed paragraph for each of the two species. The common name for E.tetragonum, is square stemmed willow herb, and we shouldn’t be surprised to read that it has a square stem, though with the caveat ‘at least below’. You might well think if this is the case shouldn’t it be easy? E.tetragonum has a square stem (at least below) and E.obscurum doesn’t, end of story? Surely? Certainly, if the plant is large and robust then the stem shape is more evident, but for smaller plants it isn’t that easy. For a start the stem of Epilobium tetragonum is not square in the Lamiaceous sense, rather it is 4-angled and I think it CAN be confused with a rounded stem if the plants are small. Also, if you come across a number of plants potentially of both species mixed together it is not at all an easy task to separate them objectively on the basis of stem shape. In the field I have agonised over enough of these plants to think that, despite the common epithet, we need more than stem shape to separate these two. Fortunately reading further into the paragraphs on page 433 we find it.

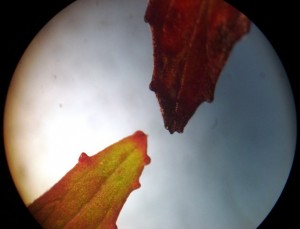

First, leaf size and especially leaf shape. The leaves of E.tetragonum are narrow, often less than 1 cm wide, linear lanceolate and often held erect. In contrast, leaves of E.obscurum are usually more than 1 cm wide, ovate-lanceolate and rounded at the base and not held erect. This can be very useful for well grown specimens, but again, with smaller plants with only a few leaves, there is still room for confusion.

Reading on we find, what for me is the clincher and this is the hydathode. These are little knobbly outgrowths on the margin of leaves of many species. Often only visible using a hand lens and only when we htl (as we often need to do when keying plants from vegetative characters). Hydathodes (I seem to recall) play a role in the water balance of the plant, but for vegetative ID where would we be without the hydathode? I often ask my students that question, and they give me a strange look. But here is a case in point.

If we take several intact leaves from our plants, however small they may be, and if we examine the leaf apices then, in E.tetragonum we find three little hydathodes, whilst in E.obscurum we find just one! Now when this works and we can separate thesetwo species as small non-flowering plants growing side by side in the field then it is very satisfying indeed – and not an ornamented seed coat in sight!