After reading Fay’s blog on the holm oak (Quercus ilex) under attack, I – like you – was in a better position to look for and recognise leaf-mining beasties on campus. What better way to follow her blog than to look at the handiwork of Ectoedemia heringella in more detail…

Ectoedemia heringella larval mines on the leaves of a Quercus ilex tree, Christchurch Road. © by Waheed Arshad, 2014.

Leaf-mines can be categorised into two types: gallery and blotch. Both types offer quite self-explanatory descriptions, but mines can often start as gallery mines, and then widen to eventually form a blotch mine. These characteristic tunnels are created between the epidermal cell layers of a leaf. Most are created by the internal feeding of lepidopteran larvae, but others are the result of coleopteran, dipteran or hymenopteran larval stages. Typically, the head of a leaf-miner larva is wedge-shaped to help separate the epidermal layers, and the legs are small and reduced, as are the antennae and eyes.

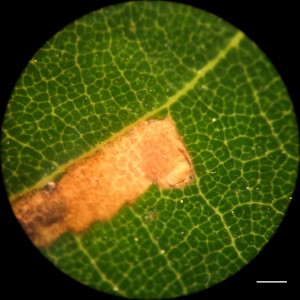

In this example, the mine starts by the centre of the leaf, slowly making its way towards the outer edge before returning to the centre again. Scale bar = 2 mm.

© by Waheed Arshad, 2014.

In the case of E. heringella, the egg is laid on the upper surface of the leaf, often near a vein, and the mine forms a much contorted gallery. In fact, most gallery-forming leaf-miners are either Stigmella, Ectoedemia or Bucculatrix species. Blotch-forming leaf-miners, on the other hand, feature one particularly notorious and very well-known species, Cameraria ohridella (horse chestnut leaf-miner), which has become an all too familiar sight by late summer.

The perforation in the leaf epidermis indicates where the larva will have emerged after its development, suggesting this mine is one from a previous year. Scale bare = 1 mm.

© by Waheed Arshad, 2014.

Another aid in miner identification is the way the larval frass is deposited during mine formation. Frass is dispersed either in a linear fashion (a line following the centre of the developing mine) or dispersed (spread within the mine). However, frass patterns or distributions in older mines can often be misleading, as the frass dries and falls to the lower part of the leaf-mine.

If you’re interested, searching for leaf-mines will always be productive! Familiarity with the larval food- or host-plant is essential, as is a bit of background research prior to heading out. As summer progresses, the number of species to be found can increase significantly. What’s more, there are also a good number of micro-moths mining through the needles of various Pinus species, with Scots Pine (P. sylvestris) probably being the most “productive” of all.

Deciduous or evergreen, a lot of trees in urban areas, parks or gardens will probably hold at least one species of leaf-miner! So if you’ve ever wondered what the very hungry caterpillar really ate, now you know…

Is it time this famous children’s book was re-written?

Useful literature

Should you find any interesting mines and would like to know which species is causing them, the following resources are useful:

– The identification of leaf-mining lepidoptera on the British Leafminers website

– Greenwood, P. and Halstead, A. (2009) RHS Pests & Diseases: The Definitive Guide to Prevention and Treatment. Dorling Kindersley.

– Nieukerken, E. J. (1985) A taxonomic revision of the western Palaearctic species of the subgenera Zimmermannia Hering and Ectoedemia Busck s. str. (Lepidoptera, Nepticulidae), with notes on their phylogeny. Tijdshrift voor Entomologie 128: 1–164.

– UK Fly Mines website – the leaf and stem mines of British flies and other insects