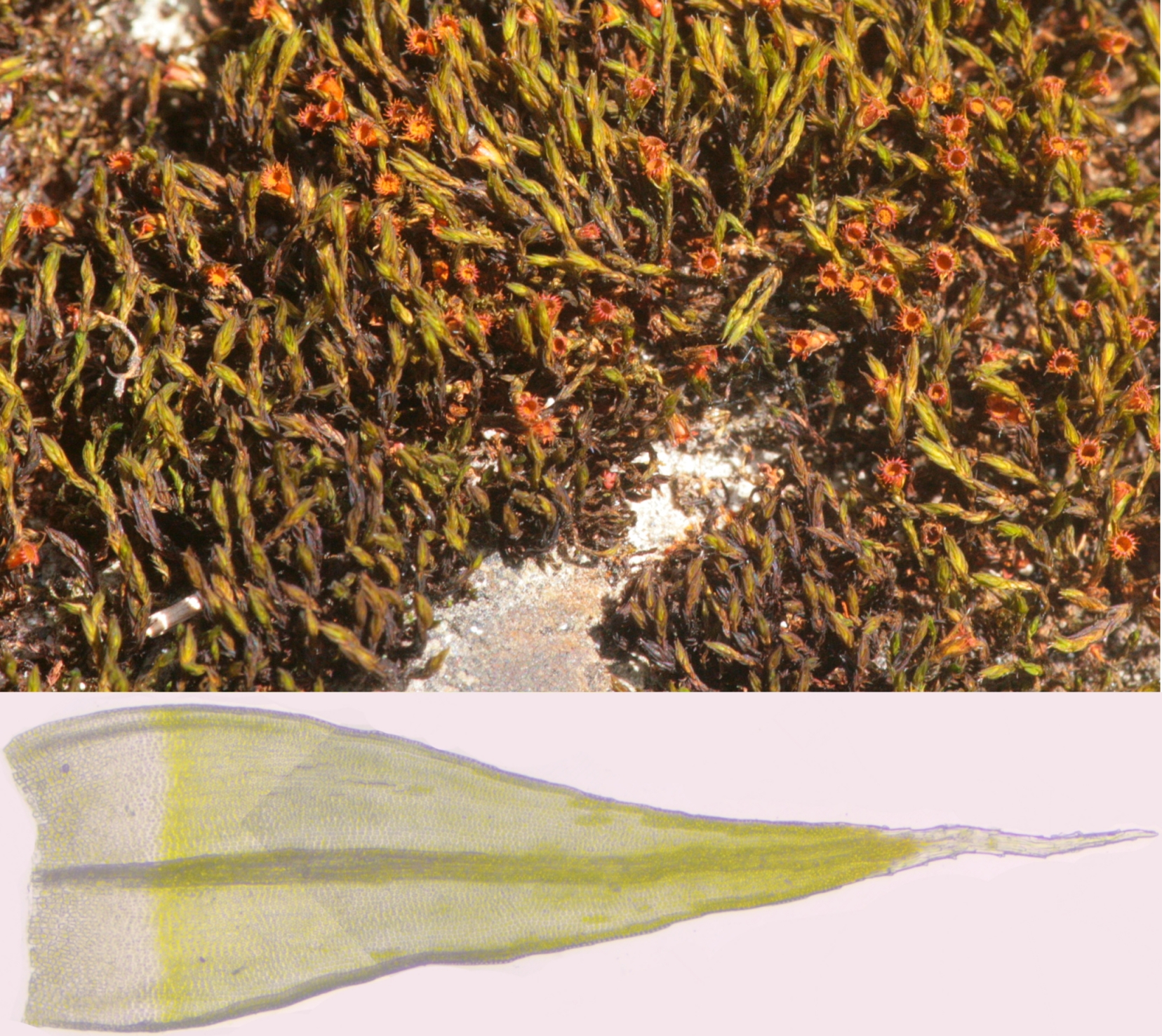

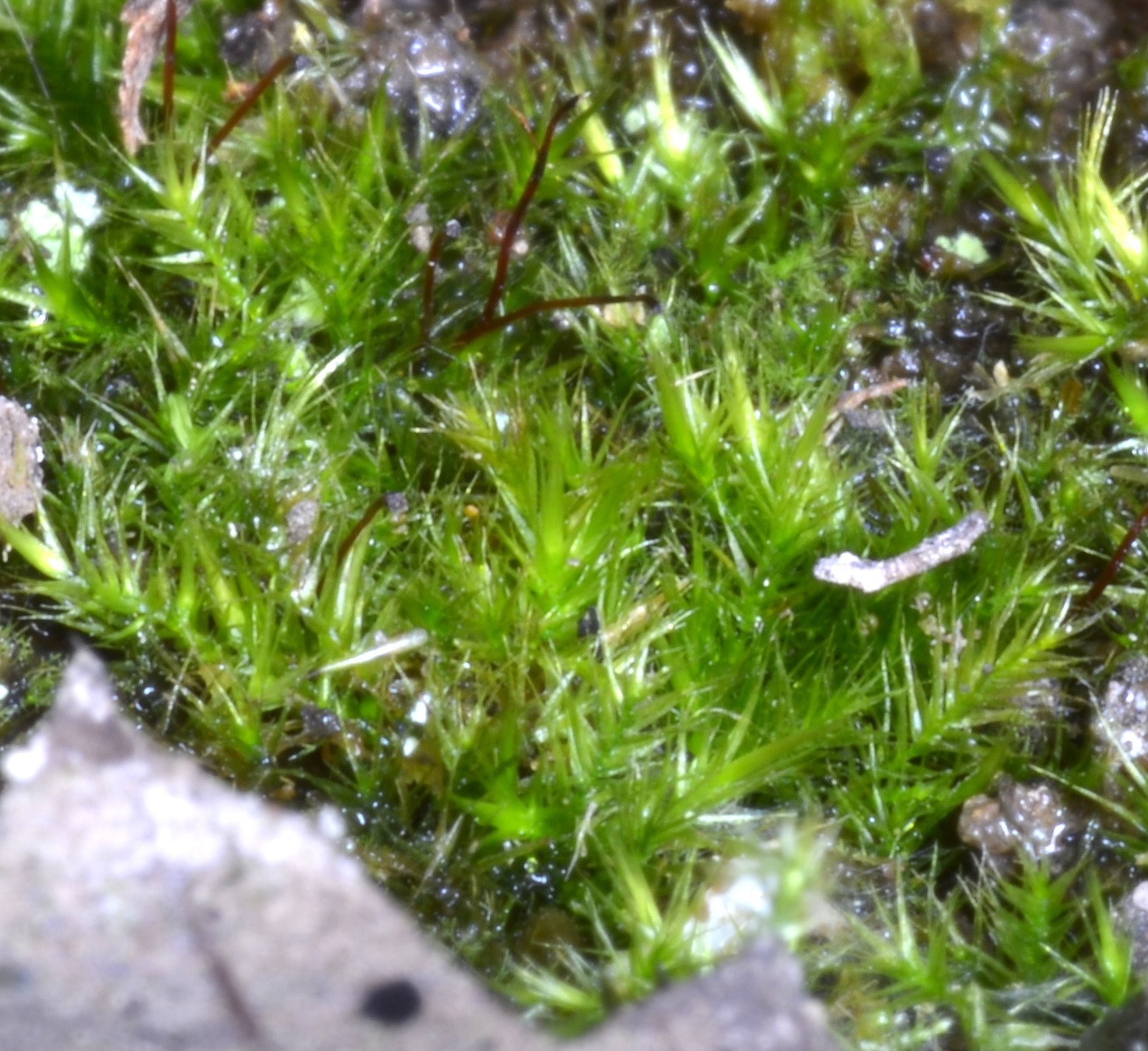

A selection of acrocarps growing on concrete: Orthotrichum cupulatum, O. diaphinum, Grimmia pulvinata, Tortula muralis, Syntrichia montana, Bryum argenteum and B. dichotomum. Image by D. Morris

3. Saxicolous Mosses

This is the fourth in a series of posts exploring the mosses and liverworts (bryophytes) of Whiteknights campus. My first three posts described the rich flora of bryophytes growing on trees (epiphytes) on campus. In this post attention is turned to mosses growing on stone, including walls and other man-made rock-like surfaces.

Like the branches and trunks of trees, stone surfaces are too hostile for vascular plants to colonise, but there are many moss adapted to grow on stone (saxicoles). The species covered in this post are mostly the very commonest saxicolous mosses, but a few are rarer on campus and one is decidedly rare in this part of the country. In lowland England there are few saxicolous liverworts, certainly none on campus.

The round hoary-looking cushions of Grimmia pulvinata are ubiquitous on urban walls. The abundant capsules on short arched setae are usually present and are characteristic. Image by D. Morris

There are no natural rock outcrops at Whitetknights but there are many excellent artificial rocks, namely walls and the like. Bryophyte communities on walls can be incredibly beautiful and diverse, and are amongst the best habitats to bryologise in urban situations. It should be noted that to successfully bryologise a wall one needs to cultivate a certain confidence in ones eccentricity, for having ones nose to concrete can excite comment and strange looks from passers by to the embarrassment of which one should become immune.

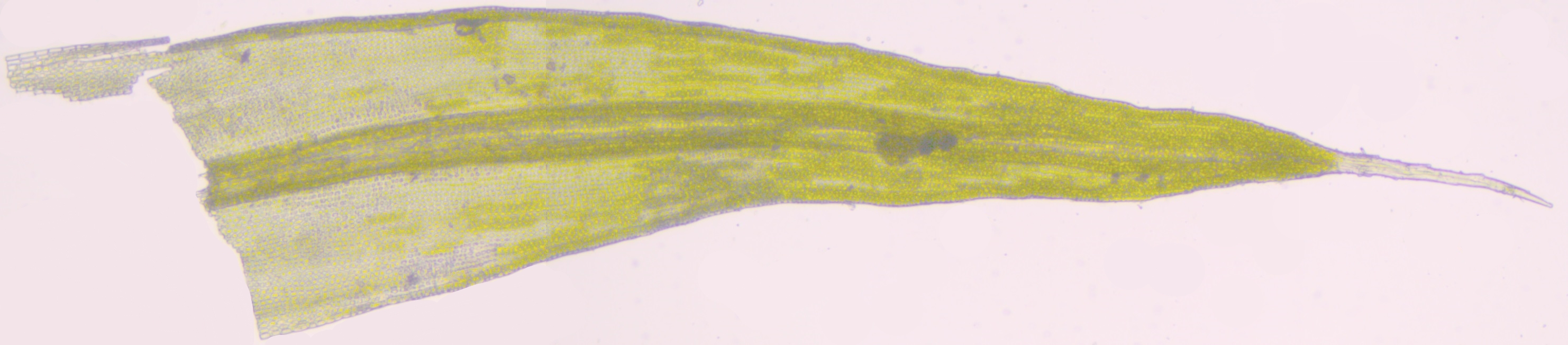

I defy you to find a wall on campus that hasn’t one or both of Tortula muralis and Grimmia pulvinata. G. pulvinata and T. muralis are widespread generalist saxicoles (they are occasionally found on trees), and are typical members of two families featuring strongly in this post: the Pottiaceae and Grimmiaceae, respectively. Members of these families often bear long narrow silvery hair-like points at the ends of their leaves, presumably an adaptation to maximise water retention. This is particularly evident in G. pulvinata, whose hair points give the tight cushions of this plant a hoary look.

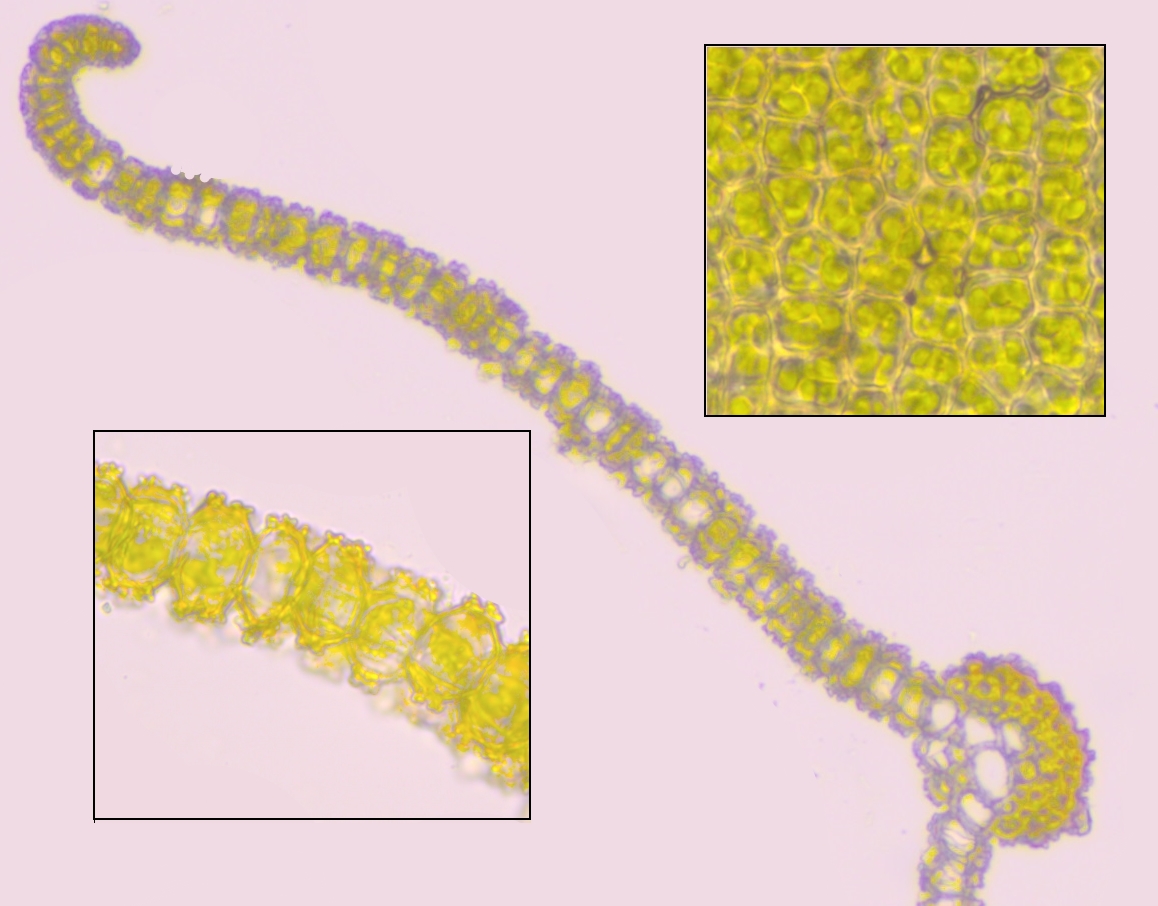

Leaf section of a common member of the Pottiaceae, Syntrichia ruralis, showing recurved margin (x200). Inset left: mid-leaf cells in section showing papillae on outer faces (x400). Inset right: cells with papillae seen from lower surface of leaf (x400). Image by D. Morris

The structure of the leaf tip is very different between the two families: in the Pottiaceae the tip is actually the nerve of the leaf extended beyond the lamina (termed excurrent), while in Grimmiaceae the nerve ends just below the end of the lamina and the leaf itself is elongated and clear. The difference in leaf cells between the two groups is also very marked. In Pottiaceae the cells are more or less round and their external walls are typically patterned by irregular bumps (papillae): these papillae scatter light unevenly from the leaf producing a matt appearance. While cell features are not visible in the field, the dull colouration of Pottiaceae produced by papillae is quite obvious, and is characteristic. In addition to their colouring, the leaves of members of the Pottiaceae are often tongue-shaped, that is with parallel sides and a rounded apex, as seen in T. muralis.

The long, opaque, tongue-shaped leaf of Tortula muralis (x100). As is clear from this underside view, the long tip is an excurrent nerve. The margins are strongly recurved, seen here as an opaque border. Image by D. Morris

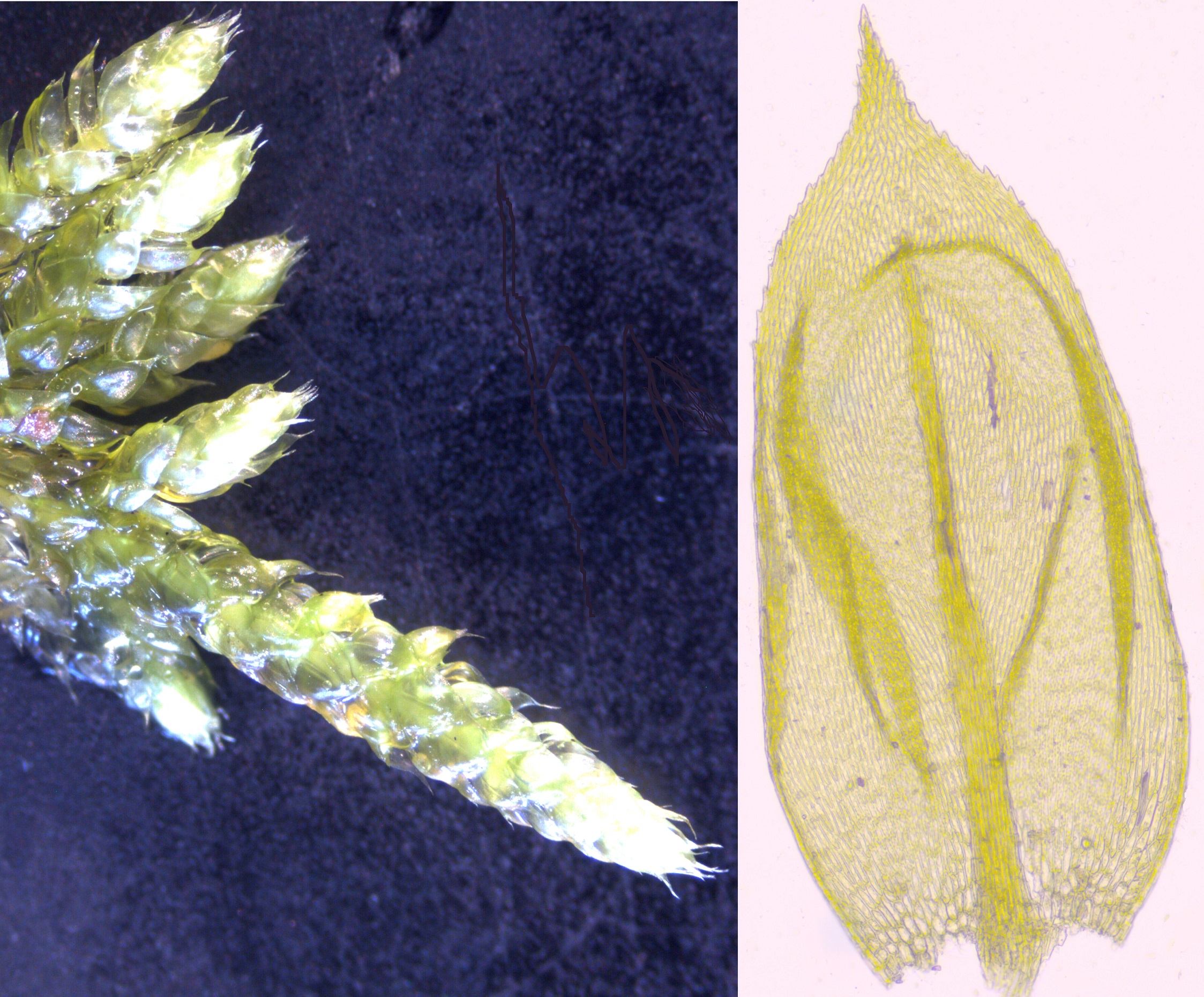

The lanceolate leaf of Grimmia pulvinata with nerve ending below the tip (x100). The leaf is quite abruptly curved into the tip which is drawn out. Inset: Sinusoidal mid-leaf cells (x400). Image by D. Morris

The leaf cells of members of Grimmiaceae are rectangular, without papillae and often have more or less wavy margins (sinusoid). Many species in this family are saxicolous, Grimmia exclusively so. In contrast to Tortula and allied Pottiaceae, the leaves are often lanceolate, i.e. for most of its length the leaf is tapered toward the tip.

In the earlier account of Orthotrichum on campus I omitted the two saxicolous species we have with us. O. anomalum is a common moss of walls, so-named because its setae are anomalously long for an Orthotrichum, holding the capsule well clear of the leaves (as in O. pulchellum). The less common O. cupulatum can be distinguished by the short seta holding the capsule just protruding from the leaves. If the silvery leaf-tip is overlooked, confusion is possible with O. diaphinum, which although a common epiphyte can be abundant on walls in urban areas. It likes nutrient rich substrates, so is equally happy on base-rich barks (e.g. elder) or urban walls drenched in the exhaust fumes of passing cars.

The exposed face of this retaining wall has only scattered patches of acrocarps such as Schistidium crassipilum and Orthotrichum anomalum. The shaded face allows pleurocarps such as Cirriphyllum crassinervium, Homolathecium sericium and Rhynchostegium confertum to thrive. Image by D. Morris

Cirriphyllum crassinerviumWalls and similar structures are interesting habitats to contemplate the ecology of mosses. Bryophytes are generally very sensitive to humidity (see post one), so that quite different species assemblages may be found on opposite sides of the same wall or within shelter. Well sheltered places are suitable for colonisation by mat-forming pleurocarps, while exposed stone supports mosses specially adapted to the rigours of this situation, usually upright tuft-forming acrocarps.

In addition to the aspect of the wall, there is a further fundamental factor governing its moss flora, pH. While G. pulvinata and T. muralis have no particular preference, saxicoles in general strongly favour one or the other of acid or basic stone. If you are new to mosses, then properties of their preferred substrate, pH especially, is a good way to group species in your mind.

There is no shortage of habitat on campus for mosses of lime-rich rock thanks to the prevalence of concrete. The best locality for calcicolous saxicoles is the Chemistry Department car park. The bollards in particular are gloriously well endowed with mosses.

There is no shortage of habitat on campus for mosses of lime-rich rock thanks to the prevalence of concrete. The best locality for calcicolous saxicoles is the Chemistry Department car park. The bollards in particular are gloriously well endowed with mosses.

Left: Syntrichia ruralis growing in a paving crack. Right: the saw-toothed excurrent nerve (x200). Images by D. Morris

A common feature of basic stone is the genus Syntrichia (see also an earlier post), either S. ruralis or S. montana (S. intermedia). These species look like larger versions of T. muralis: one of the main differences is the mean looking teeth on the hair point, absent in Tortula. S. ruralis is quite a big moss, often forming tall golden-green patches with the leaves bent well back from the stems. The margins of the leaves are turned downwards (recurved) from the base of the leaf to near the tip, which distinguishes it from S. montana, in which the margin is recurved only halfway or so. This is also usually smaller and green, and the leaves are constricted below the middle and are held at a shallower angle to the stem than in S. ruralis. Recurved margins can take some practice to see with a lens, but it is quite clear in Syntrichia (see the images of a leaf of T. muralis and a section of a leaf of S. ruralis above).

Top: Schistidium crassipilum showing habit and abundant capsules. Image by H. Schachner [CCO], via Wikimedia Commons. Bottom: the lanceolate leaf with strong hair point. Image by D. Morris

A further very common lime-loving moss of concrete on campus is Schistidium crassipilum, a highly distinctive member of the Grimmiaceae. The sprawling shoots can form very extensive loose mats, as for instance outside the Lyle Building. The most distinctive feature of this moss (indeed of the genus) is the capsules, which are always present and are immersed amongst the leaves (like O. affine). Although bearing a stout hair point, the leaves are longer and more tapering than those of G. pulvinata, not that one could confuse the two.

The upland acid-rock-loving Grimmia trichophylla

quite happy on a lowland sarsen stone in the Wilderness. Image by D. Morris

Acid rock is rare in lowland England, founded as it is on various kinds of limestone, but in upland Britain the flora of acid rock is very rich, with Grimmiaceae very apparent. Nevertheless, the use of acid rock for landscaping affords some upland species a rare lowland habitat, as seen on campus. On the boulders in the area of the Wilderness known as the grotto can be found the locally rare G. trichophylla, a common moss in the uplands. These boulders are of an acid sandstone known as sarsen, boulders of which once occurred in colonies of many thousands over the downs of Wiltshire and west Berkshire. If only campus had Hedwigia stellata or G. decipiens as the sarsen stones of Fyfield Down in Wiltshire do!

The longly lanceolate leaf of Grimmia trichophylla (x50). In contrast to G. pulvinata the leaf is gradually tapered into the tip. The leaf of Schistidium crassipilum is less longly tapering and distinctly triangular. It is also strongly lime-loving and has abundant immersed capsules. Image by D. Morris

Left: the spiky round shoots of Cirriphyllum crassinervium. Right: the characteristic leaf shape of the genus (x50). The creases arise from the strongly concave leaf being squashed under a cover slip. Images by D. Morris

On the same group of rocks can also be found two saxicolous pleurocarps. They are quite common but attractive mosses. Cirriphyllum crassinervium is a robust moss and covers the shady parts of many of the boulders. At a casual glance you might mistake it for a Hypnum species, but a closer look shows many long points sticking upwards from the tip of the shoot. The leaves are strongly concave and sharply pointed, an unmistakable feature of Cirriphyllum. It also possesses a very strong nerve, which is missing in Hypnum.

A number of quite common mosses possess pleasingly long lyrical names; our final moss, Rhynchostegiella tenella, is a fine example. This pleurocarp thrives in well sheltered situations on base-rich rock: I assume that there is some source of lime in the cranny where this plant grows, perhaps from mortar used to build the grotto, else its appearance on otherwise acid rock is unusual. The upright shoots of R. tenella 2mm or so high look a little like tiny acrocarps, but these are branches: the primary stems are pressed against the substrate. This habit and the very long, needle-like leaves are unique.

Fabulous post and fabulous mosses! So beautifully presented here how could anyone resist them?! Dr M

Saxicolous liverwort: last year I found Cololejeunea minutissima growing on some of the small sarsen stones in the wood near the Grotto.

Thank you, Sue, that’s interesting. I will have a look for it, not having seen it on stone before.

You can’t miss it! I revisited the “stone circle” and found that C minutissima is spreading fast for such a small plant. Some of its mats now support other bryophytes. In other humid places C minutissima seems happy to colonise smooth acidic surfaces such as youngish oak bark. I’ll be watching to see whether that allows a more diverse flora to develop where previously nothing much would grow.

I found it. It is quite conspicuous as you say. I will look out for Metzgeria consanguinea.