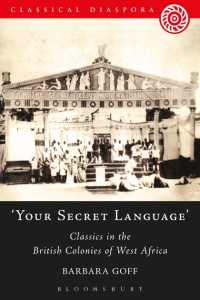

Last week saw the publication of my new book Your Secret Language: classics in the British colonies of West Africa (Bloomsbury 2013). It contributes to the Departmental research cluster in ‘Reception and Classical Tradition’, and to the Faculty research theme of ‘Language, Text and Power’. Above and beyond these aspects, I have found it a fascinating story to research and write.

Last week saw the publication of my new book Your Secret Language: classics in the British colonies of West Africa (Bloomsbury 2013). It contributes to the Departmental research cluster in ‘Reception and Classical Tradition’, and to the Faculty research theme of ‘Language, Text and Power’. Above and beyond these aspects, I have found it a fascinating story to research and write.

The classical languages, literature and history formed part of the cultural equipment which European colonisers called upon in order to justify their imperial ambitions, but within the complex and assertive societies of nineteenth-century West Africa, classical education quickly became a weapon to use against colonisers. The Church of England, which was very early on involved in educating colonised West Africans, put a premium on teaching the ancient languages, including Hebrew, in order to enable converts to read and preach the Bible themselves, and missionaries were delighted when Africans showed themselves highly adept at Latin and Greek. They and the colonial establishment generally were less pleased when Africans used their classical training to qualify as lawyers, churchmen, teachers and journalists and then to agitate against colonialism. Several African commentators noted the ancient relations between Africa and Greece, anticipating Martin Bernal’s analysis by many decades and complicating the notion of the classical tradition.

In the early twentieth century the colonial establishment often reacted by trying to withhold classical education from Africans and teach them agriculture instead. Africans usually saw this as an attempt to keep them subordinate, as ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’, and put up prolonged and articulate resistance. The struggles over classical education continued, and eventually led to a situation in which Classics was the first degree offered in the post-war University of Ibadan. Although the subject lost most of its prominent position after independence, when Africans seized the opportunity to study many other subjects that colonialism had not imported, there are still departments of Classics in Nigeria, Ghana, and Sierra Leone, as well as in several other African states. We are planning to welcome one of the lecturers from Nigeria as a visiting researcher, who will be in Reading in 2014.

Researching this book, I have felt privileged to learn more about the history of my discipline and to see what it has meant within the making both of the colonial and the postcolonial eras. The history has also deepened my understanding of the West African adaptations of Greek tragedy about which I wrote in the co-authored Crossroads in the Black Aegean: Oedipus, Antigone and dramas of the African diaspora (Oxford 2007). In addition, I have felt proud to be part of a Department where ‘classics’ signifies both the ancient world and its varied manifestations in the modern.