Dr Nick West writes:

The words of Papyrus Chester Beatty IV, a short text extolling the immortality of writers, still resonate after 3000 years or so:

“Their portals and mansions have crumbled, their Ka servants (mortuary cult priests) are gone; their tombstones are covered with soil, their graves are forgotten. Their name is pronounced over their books, which they made while they had being; good is the memory of their makers, it is forever and all time!”

If you go down to Typography today, you’re in for a big surprise. There’s lots of marvellous things to see and curiosities on display.

Unmetrical allusions to teddy bears aside, the department holds a real treasure for me (among many others). One I’ve been dying to have myself, namely, a Book of the Dead papyrus.

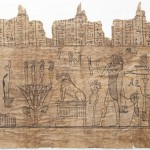

The Palmer papyrus may be a tiddler as BD papyri go (just over 13 feet long) but it’s still close to being three of me lying down. I didn’t measure precisely; you get funny looks lying prostrate in a corridor.

Still, although it is not the 100 feet plus leviathan of which the British Museum can boast, the Palmer papyrus can rival the BM’s collection. Only one papyrus from the BM (and apparently no other papyrus in the world, according to my advisors) compares with our papyrus in Reading because it is one of only two that can be called ‘hybrids’.

Over the millennium long evolution of the Book of the Dead’s development there were several distinct styles of laying out a manuscript. These set styles do not seem to have been mixed … that is with the exception of P. BM EA 9904 and the Palmer papyrus.

I had no idea about this when I went to visit and when the protective covers were removed I had the biggest shock of my life … a mixed style papyrus.

The first portion is laid out in the horizontal ‘Theban style’ and written in Egyptian hieratic (a shorthand script based on hieroglyphs) while the remainder is written out in hieroglyphs either in vertical columns or horizontal rows.

My mind was totally blown: nothing I had learnt about the Book of the Dead prepared me for this moment. Once I’d recovered from my initial stupor it occurred to me that even though this is a reasonably late papyrus (Ptolemaic period circa 200 BC) I was still looking at a text that was a century or two more than 2000 years old! It never sounds much in print but the immediacy of this statistic really hits you when you are gaping at it!

This brings me back to the quotation from Papyrus Chester Beatty, composed around the time the Book of the Dead was being put together. Although the top quarter of the papyrus is lost the name of the papyrus’ owner remains in a number of places: Heru-ibu the daughter of Ta-neferu.

Reading out her name, as well as portions from the papyrus, brought it home to me that the modern term ‘Book of the Dead’ is a misnomer in several ways.

Not only does the modern name we give to a collection of texts the Egyptians called ‘spells for going forth by day’ miss the mark because the original title emphasises new life, the term hides the fact that the Book of the Dead is far from dead.

Even now scholars are comparing ever more manuscripts and deducing many regional traditions of this corpus. There may even be other eccentric people like me compiling their own manuscript.

In reading Heru-Ibu’s papyrus in its preserved state, we give her, and the other owners of BD manuscripts such as Ani, Nebseny and Hunefer, the immortality their papyri had intended.

Just as Papyrus Chester Beatty IV says, “good is the memory of their makers, it is forever and all time”!