On Wednesday 5 February 2014, Dr Katherine Harloe will give a public talk with Ian Jenkins of the British Museum on the topic ‘Winckelmann: Art and Death in Enlightenment Europe’. Below she discusses some aspects of Winckelmann’s life and work, his death, and what led her to make him the subject of her recent monograph.

On Wednesday 5 February 2014, Dr Katherine Harloe will give a public talk with Ian Jenkins of the British Museum on the topic ‘Winckelmann: Art and Death in Enlightenment Europe’. Below she discusses some aspects of Winckelmann’s life and work, his death, and what led her to make him the subject of her recent monograph.

Around ten in the morning on 8 June 1768, a commotion disturbed the staff and guests at Trieste’s Osteria Grande. The hotel steward, Andreas Harthaber, was first to react. He was cleaning the main dining room when he heard a loud thump from room 10 above. Running upstairs, he threw open the door to see the guest of that room stretched out on the floor, a noose around his neck. The inhabitant of the neighbouring room knelt above him, one hand on his chest, the other brandishing a bloodied knife. On seeing Andreas the assailant jumped up, pushed his way out of the door and fled from hotel and city. Doctors were called but it was too late to save the victim, who died from his injuries some hours later.

Such was the unexpected and brutal end of a man who was known to the Osteria staff simply as ‘Signor Giovanni’, but was soon revealed to be a person of some consequence. Among his effects were gold and silver medals bearing likenesses of Maria Theresa, Empress of Austria, and her son, the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II. A passport, issued in Vienna some two weeks previously, identified its bearer as ‘Johannes Winckelmann, Prefect of Antiquities in Rome, on his way back to the Holy City’.

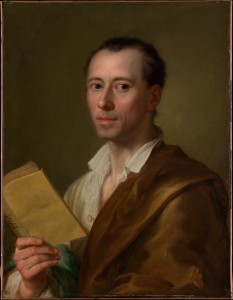

The notoriety of this murder is so great that the Grand Hotel Duchi d’Aosta, which now stands on the site once occupied by the Osteria Grande, still carries details of it on its homepage . The murderer, Francesco Arcangeli, had unwittingly killed one of the leading lights of Enlightened antiquarianism and connoisseurship. Contemporary opinion of Winckelmann is best summed up in an early nineteenth-century French engraving, a copy of which is displayed in the case devoted to Winckelmann in the British Museum’s Enlightenment Gallery. The main image, which is based on a portrait Winckelmann’s great friend, the neoclassical painter Anton Raphael Mengs, shows him dressed humbly, reading an edition of Homer. Below, between copies of two of his most famous works (the Description of the Apollo Belvedere and the History of the Art of the Ancients), a legend declares ‘In the midst of Rome, Winckelmann lit the flame of the rational study of the works of the Ancients’.

The notoriety of this murder is so great that the Grand Hotel Duchi d’Aosta, which now stands on the site once occupied by the Osteria Grande, still carries details of it on its homepage . The murderer, Francesco Arcangeli, had unwittingly killed one of the leading lights of Enlightened antiquarianism and connoisseurship. Contemporary opinion of Winckelmann is best summed up in an early nineteenth-century French engraving, a copy of which is displayed in the case devoted to Winckelmann in the British Museum’s Enlightenment Gallery. The main image, which is based on a portrait Winckelmann’s great friend, the neoclassical painter Anton Raphael Mengs, shows him dressed humbly, reading an edition of Homer. Below, between copies of two of his most famous works (the Description of the Apollo Belvedere and the History of the Art of the Ancients), a legend declares ‘In the midst of Rome, Winckelmann lit the flame of the rational study of the works of the Ancients’.

My own fascination with Winckelmann began some eight years ago, when I was researching a project on changing conceptions of classical scholarship from the seventeenth century to today. My experiences as an undergraduate classicist at Oxford, and then as a student of early modern history at Cambridge, had alerted me a strange disjunction between the notion of classics held by an early modern thinkers like Thomas Hobbes and those of my teachers and contemporaries. In the early modern university, study of the Greek and Roman classics was an elementary discipline, taught to inculcate principles of good style and virtuous conduct through the study of uplifting examples. This seemed a far cry from classics as I understood it, as a non-utilitarian, historical discipline aimed at recovering and reconstructing of the ancient world in all its aspect.

My attempts to account for this change led me back time and time again to Winckelmann’s name. His researches in 1750s and 1760s Rome were key to transforming the academic study of classics, popularising the study of ancient objects and turning it from a mainly literary discipine into the holistic study and reconstruction of ancient cultures. Winckelmann was the first to bring together interpretation of thousands of different artefacts from ancient Egypt, Etruria, Greece and Rome into an overarching story of the rise and decline of ancient cultures, and to connect differences in their characteristics and quality (‘style’) to the political and social conditions of their time. Even if many of his judgements now seem to have been motivated by prejudice, the ambition of his historical ‘system’ – as well as some of its details, such as his broad distinctions between the archaic, classical and Hellenistic periods – have exerted a great influence on the concepts and categories of classical scholarship to this day.

Yet, in the eighteenth century as today, commentators were just as fascinated by other aspects of Winckelmann’s life and character: his biography, with its startling ascent from rags to riches, the overt homoeroticism of some of his most famous writings, and of course his bloody end. Winckelmann inspired the generation of Goethe and Schiller; French revolutionaries hailed him as a champion of liberty; and in the early twentieth century he inspired novellas by German Nobel laureates Thomas Mann (‘Der Tod in Venedig’) and Gerhart Hauptmann (‘Winckelmann – das Verhängnis). My research to date has focused on Winckelmann’s impact on scholarship, but this Enlightenment life and personality is fascinating from any number of angles.

All are welcome to attend Dr Harloe’s talk in the British Museum’s Enlightenment Gallery on Wednesday 5 February at 1:15pm.