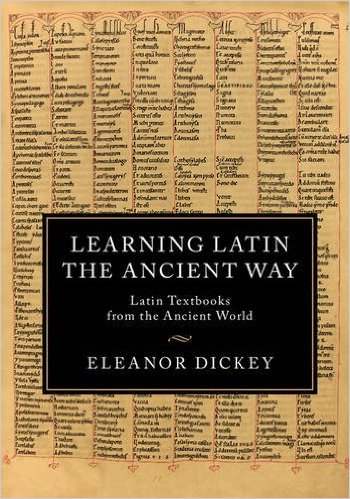

The past few months have been exciting ones for the Classics department owing to a blitz of media attention covering the publication of Professor Eleanor Dickey’s book Learning Latin the Ancient Way as well as the annual Reading Ancient Schoolroom.

It started in February with an article in the Guardian and lasted until April, when the CBC Radio Canada broadcast a half-hour interview with Professor Dickey; along the way we featured on national TV and radio as well as the Times, the Telegraph, and numerous European publications. The final tally was (as far as we know) 3 printed newspaper pieces, 11 online newspaper pieces in 6 languages, 2 national TV broadcasts, 2 BBC South TV broadcasts, and 6 radio broadcasts (4 in UK, 1 in US, 1 in Canada).

Here is the full list:

Wednesday 10th February

- Guardian online (Alison Flood): http://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/feb/10/ancient-greek-manuscripts-reveal-life-lessons-from-the-roman-empire

- Πρώτο ΘΕΜΑ online (in Modern Greek): http://www.protothema.gr/world/article/552202/arhaia-ellinika-heirografa-apokaluptoun-tin-zoi-stin-romaiki-periodo/

- Ziare.com online (in Romanian): http://www.ziare.com/cultura/istoria-culturii-si-civilizatiei/detalii-inedite-din-roma-antica-manuscrise-despre-baia-publica-targuiala-din-piata-si-rudele-baute-1408232

Thursday 11th February

- Guardian print version (Alison Flood), p. 6

- BBC World Service radio: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p03j7gc7

- BBC Radio Wales (c. 4:30 pm)

- National Public Radio (US) ‘The World’ programme

- Telegraph online (Alice Philipson): http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/italy/12152081/Ancient-Greek-manuscript-reveal-Roman-life-lessons.html

- Jutarnji online (in Croatian): http://www.jutarnji.hr/udzbenici-iz-antike-pokazuju-kako-su-se-nekad-ucili-strani-jezici-studenti-ucili-kako-postupiti-s-pijanim-clanom-obitelji-te-kako-udijeliti–socne–uvrede/1517987/

- ΚΕΡΔΟΣ online (in Modern Greek): http://www.thetoc.gr/koinwnia/article/arxaio-elliniko-egxeiridio-paradideimathimata-zwis

Friday 12th Feburary

- The Times, p. 23.

- Times online (Jack Malvern): http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/arts/article4688596.ece (subscription only)

- BBC One South TV, 1:40 and 6:50 pm.

- BBC Radio Four World at One (just before 2 pm): http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b070j7ld – play at 42 minutes in.

- BBC Radio Scotland (4:15 pm)

Saturday 13th February

- BBC 1 TV, BBC Breakfast (around 7:30 am, and/or at 9:50 am)

- In.gr online (in modern Greek): http://news.in.gr/features/article/?aid=1500057932

Sunday 14th February

- BBC 1 TV, 2:24 am

Wednesday 17th February

- Gazete Yeniyüzyil online (in Turkish): http://www.gazeteyeniyuzyil.com/haber/kultur-sanat/romalilarin-hayat-bilgisi-el-yazmalarinda-16447

Saturday 20 February

- Announcement of Naples ‘Presentazione libro’ sent out on Notiziario Italiano di Antichistica

Monday 22nd February

- El Español online (in Spanish, by Lorena G. Maldonado): http://www.elespanol.com/cultura/libros/20160222/104239646_0.html

Thursday 25th February

- Times Higher Education magazine p. 49 (Karen Shook, ‘New and noteworthy’ section, first item) (also online at https://www.timeshighereducation.com/books/reviews-new-and-noteworthy-25-february-2016)

Tuesday 1st March

- ‘Presentazione libro’ in Naples (public event in which book was discussed by a pair of Naples Classicists; in Italian)

Monday 7th March

- Reddit AMA: https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/49cvdy/iama_classics_professor_who_has_travelled_around/

Friday 1st April

- CBC radio Canada: http://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/the-current-for-april-1-2016-1.3516122/translations-of-ancient-latin-give-unique-insights-into-roman-culture-1.3516154

For more information on the Reading Ancient Schoolroom, see http://www.readingancientschoolroom.com.

Classics students – and those with a taste for sub-par Oliver Stone movies – will know that Alexander the Great campaigned as far as the very edges of the world as known to the ancient Greeks, in Afghanistan and India. A story which is less well know is that of the military colonists he left behind. Greek and Macedonian soldiers were settled in remote garrisons, as well as ancient cities such as Samarkand and Bactra. For almost three hundred years, the descendants of these soldiers ruled as kings in Central Asia and India, minting coins with Greek legends.

Classics students – and those with a taste for sub-par Oliver Stone movies – will know that Alexander the Great campaigned as far as the very edges of the world as known to the ancient Greeks, in Afghanistan and India. A story which is less well know is that of the military colonists he left behind. Greek and Macedonian soldiers were settled in remote garrisons, as well as ancient cities such as Samarkand and Bactra. For almost three hundred years, the descendants of these soldiers ruled as kings in Central Asia and India, minting coins with Greek legends.