On the glorious sunny evening of 29th June 2018, the Very Rev’d Professor Martyn Percy, Dean of Christ Church, welcomed Reading staff, interested scholars and other supporters to a champagne launch of Winckelmann and Curiosity in the 18th-century Gentleman’s Library, which explores the interaction and influence of Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1758), the pioneer historian, art historian and archaeologist, on the occasion of the double anniversaries of his birth and death. (https://www.winckelmann-gesellschaft.com/en/winckelmann_anniversaries_20172018).

The event also served as a finale to a very successful one-day workshop on Ideals and Nations: New perspectives on the European reception of Winckelmann’s aesthetics, organised by Dr Fiona Gatty and Lucy Russell, under the auspices of the Department of Modern Languages, Oxford University. (This was the last of our triplet of workshops on the theme Under the Greek Sky: Taste and the Reception of Classical art from Winckelmann to the present, of which Spreading good taste: Winckelmann and the objects of dissemination—in Reading on 15 September 2017—was the second). On this auspicious occasion Professor Alex Potts from University of Michigan, formerly Professor of the History of Art & Architecture at University, served as one of the workshops’ keynote speakers and proposed a toast to Winckelmann.

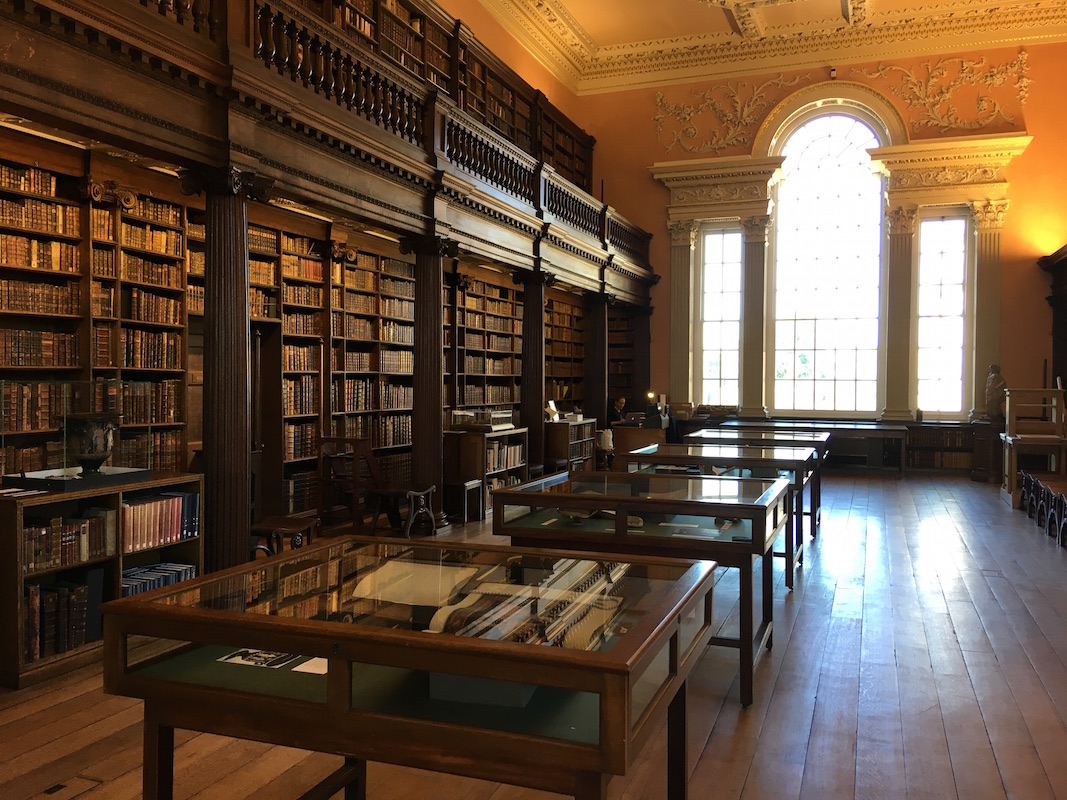

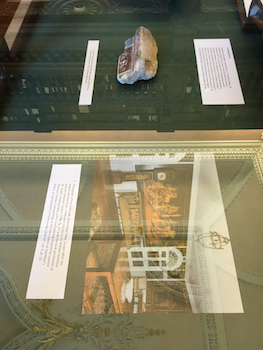

This exhibition is a collaboration between UoR Classics’ Ure Museum and Christ Church, co-curated by Reading’s Dr Katherine Harloe and Prof Amy Smith (Curator of the Ure Museum) and Christ Church’s Cristina Neagu (Keeper of Collections). The exhibition of vases, coins, gems (and casts thereof) and even a piece of painted Pompeian plaster kindly lent by the Reading Museum Service, is displayed in Christ Church’s recently restored upper library, which IS in fact the very embodiment of the collecting curiosity that Winckelmann influenced with his enthusiasm for the study of artefacts alongside texts. The library, completed in 1772, boasts large Venetian windows at either end, fittings that date mostly from the 1750s and plasterwork replicating some of the musical instruments once contained in the library.

This exhibition is a collaboration between UoR Classics’ Ure Museum and Christ Church, co-curated by Reading’s Dr Katherine Harloe and Prof Amy Smith (Curator of the Ure Museum) and Christ Church’s Cristina Neagu (Keeper of Collections). The exhibition of vases, coins, gems (and casts thereof) and even a piece of painted Pompeian plaster kindly lent by the Reading Museum Service, is displayed in Christ Church’s recently restored upper library, which IS in fact the very embodiment of the collecting curiosity that Winckelmann influenced with his enthusiasm for the study of artefacts alongside texts. The library, completed in 1772, boasts large Venetian windows at either end, fittings that date mostly from the 1750s and plasterwork replicating some of the musical instruments once contained in the library.

The exhibition is accompanied by a 134-page book, edited by Drs Harloe & Neagu & Prof Smith, with essays and a handlist of the objects on display, available from either Christ Church or the University of Reading for £10. We are grateful to the Friends of the University of Reading for funds in support of this publication.

The exhibition is accompanied by a 134-page book, edited by Drs Harloe & Neagu & Prof Smith, with essays and a handlist of the objects on display, available from either Christ Church or the University of Reading for £10. We are grateful to the Friends of the University of Reading for funds in support of this publication.

The Ure Museum staff have planned a series of outreach activities in connection with the exhibition, starting with an activity for children and their carers: The Grand Tour: How Classical art went viral in England at Christ Church on Mondays—30th July, 6th and 13th August, from 11am to 1230 pm, in Christ Church Library (OX1 4EJ). Please contact ure.education@reading.ac.uk if you are interested in participating. Details of this and other related activities can be found on the ‘Winckelmania’ research blog—https://research.reading.ac.uk/winckelmania/.