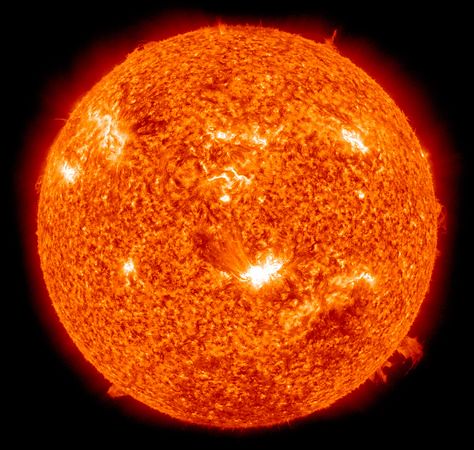

The impact of the Sun and solar wind on Earth’s technological systems has become known as Space Weather. In order to understand the impact of space weather and better forecast its occurrence it is important to gather as much information as possible. Historical data sets could help us understand space weather conditions from a time long before direct measurements of the solar wind could be made in space. The Sun has an eleven year activity cycle throughout which enormous eruptions known as Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs) occur. While there are generally more CMEs during active periods, they can occur at any time and with a range of scales. A typical CME consists of around a billion tonnes of material erupting into space from the solar atmosphere at a million miles an hour. If such a ‘solar storm’ arrives at Earth, the hot plasma (an electrified gas) is guided towards the north and south poles by the Earth’s magnetic field where it interacts with the upper atmosphere, generating spectacular auroral displays. In addition to the hazard this represents to spacecraft electronics, the resulting atmospheric heating causes the atmosphere to expand, increasing the drag on satellites and weakening the ionosphere (an electrified region of the Earth’s upper atmosphere). As this heated air circulates around the world, the ionosphere is temporarily weakened in what is known as an ionospheric storm. Unexpected changes to the ionosphere affect the efficiency of long-distance radio communication and influence the accuracy of GPS navigational systems. The most extreme space weather events occur around once per century. In order to improve our statistical understanding of space weather we must therefore look to historical datasets to augment direct observations of solar activity obtained since the beginning of the space age.

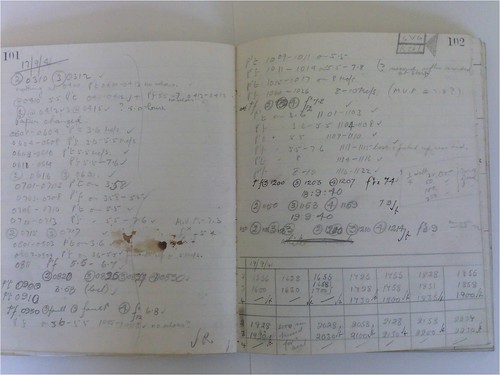

One such data set contains observations of the Earth’s ionosphere that have been carried out since the early 1930s in Slough, UK. The Earth’s ionosphere is very sensitive to changes in solar activity both through changes in solar irradiance and through the arrival of solar coronal mass ejections at Earth. This long-term dataset therefore contains the signatures of space weather events over many solar cycles. Detailed analysis of these data is time consuming as the information is contained within photographic prints and log-books containing hand-written notes that are not easily read by computerised systems.

This type of analysis is ideal for a ‘citizen science’ project in which members of the public are each encouraged to scrutinize a small section of the data. With enough effort, the sum of many small contributions (and a few large ones!) can lead to a comprehensive analysis of the entire archive. Current projects such as www.solar stormwatch.com (in which users track the trajectory of CMEs observed by the NASA STEREO spacecraft) and www.oldweather.org (which invites users to digitise meteorological information from ships’ logs) have led the way in demonstrating the enthusiasm for space weather amongst citizen scientists and in showing the power of such projects in recovering historical environmental data sets. If we can do the same for these unique ionospheric records, we will increase our understanding of the impact of space weather events and other long-term changes in the Earth’s ionosphere.