By Ray Bell,

It’s that time of year again, when sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are warming up in the northern hemisphere, which allows the tropics to become more conducive for tropical storm formation. Warm waters are needed to provide the storm’s with a source of energy. These tropical storms, if they make landfall, can become life-threatening for populations in the Caribbean, around the Gulf of Mexico and US east coast. As result of their seriousness, President Obama recently gave a statement on hurricane preparedness.

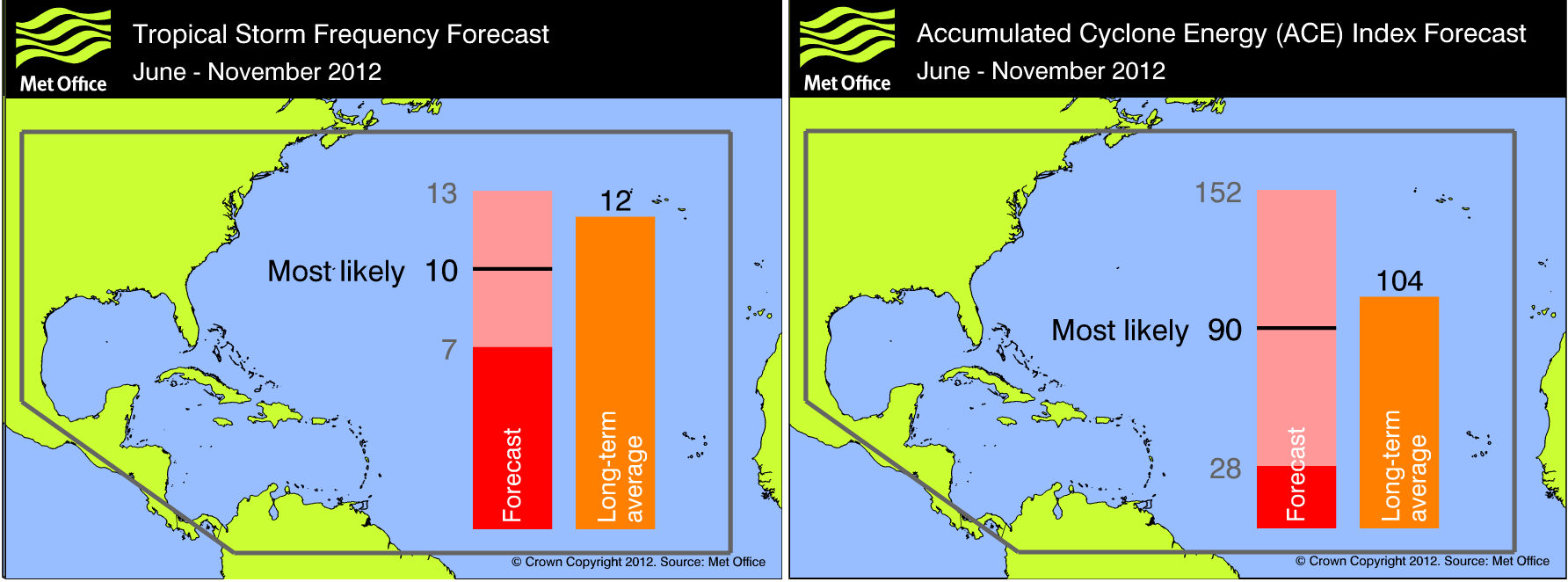

On the 24th May, the Met Office released its annual Atlantic tropical storm seasonal forecast, which runs from June – November. Their forecast predicts 10 tropical storms (70% chance, 7-13) and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index – which measures the number of storms and their combined strength – of 90 (70% chance, with a large spread of 28-152). This is slightly below the 1980-2010 long term average of 12 storms and an ACE of 104.

There have already been 2 storms (Alberto and Beryl). These do not count towards the Met Office’s forecast, which is issued from June 1st. Although this season was off to a quick start – only 1908 and 1887 had two named storms form so early in the year – the storms formed at relatively high latitudes (off the coast of Florida). They were likely to be associated with extra-tropical disturbances in a region of low vertical wind shear (a change in wind speed/direction with height, which if large enough destroys the moist column of air required for the storms development) and warm SSTs from the Gulf Stream. It is unlikely they are a harbinger for an active season.

Method

I wrote a similar blog this time last year which outlines the method the Met Office use for its seasonal forecasts and the amount of skill they have. Since 2011, the Met Office has updated its seasonal forecasting system.

The GloSea4 system has improved physics parameterisations – a way of representing sub grid scale processes. The Met Office also uses the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) seasonal forecasting system, System 4, which has an increased horizontal and vertical resolution. Both improvements are important to capture complex physical processes that cause tropical storms to form and to resolve more intense wind speeds associated with hurricanes.

Atmospheric and oceanic conditions

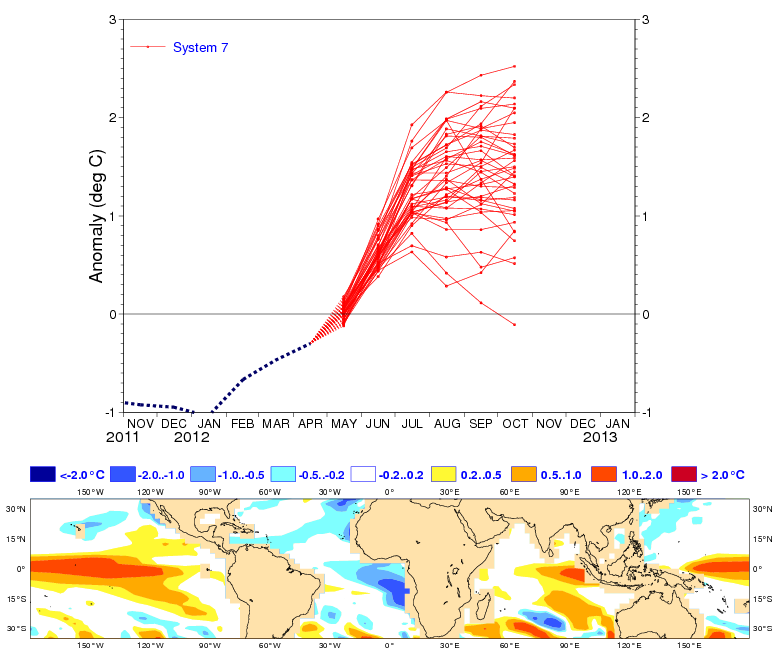

The Met Office forecast the season to be slightly below average based on the near neutral El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) conditions, which they predict will develop into neutral-El Niño conditions toward to end of the season. The uncertainty in the ENSO forecast is the likely reason for the large spread in the ACE index forecast.

Joanne Camp, climate scientist at the Met Office, said: “El Niño conditions in the Pacific can hinder the development of tropical storms in the Atlantic, so how this develops will be important for the storm season ahead – particularly from August onwards, which is normally the most active time for tropical storms.” in a recent Met Office press release.

The main mechanism how El Niño influences North Atlantic tropical storms is by increasing the 200 hPa (12 km) westerly winds (Goldernberg and Shapiro, 1996). This increases the vertical wind shear and inhibits tropical cyclone formation.

The Met Office also forecast near- to below-average SSTs across much of the tropical Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, known as the Main Development Region (MDR), during the peak of the hurricane season (August-October). The cooler SSTs, particularly off the coast of Africa, where the majority of storms form from African Easterly Waves, are likely to be less favourable for development. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) also provide great science on the atmospheric and oceanic conditions likely to be present for this season.

Other tropical storm seasonal forecasts

The table below shows other seasonal tropical storms forecasts from a range of different centres. The mean of these forecasts is for 12 tropical storms and an ACE of 98. The Met Office lies in the low end of these forecasts, likely due to their forecast for moderate El Niño conditions late in the season, which is at the high end of other ENSO forecasts.

What will this year’s tropical storm season bring?

Jeff Master’s, in his blog, poses 5 questions about the upcoming season. The most important of these is whether the North Atlantic will come out of its lull of Major Hurricane landfalls – The longest for over 140 years (see ‘Dearth of Major Hurricanes landfall’ in my previous blog).

To keep up to date with tropical cyclones, the Met Office provide a twitter feed (@metofficestorms) and a realtime storm tracker product.

I will write a blog at the end of the season looking at the validation of the Met Office’s forecast. I would also like to thank ex-Reading University student and colleague Joanne Camp for her time spent answering my questions.