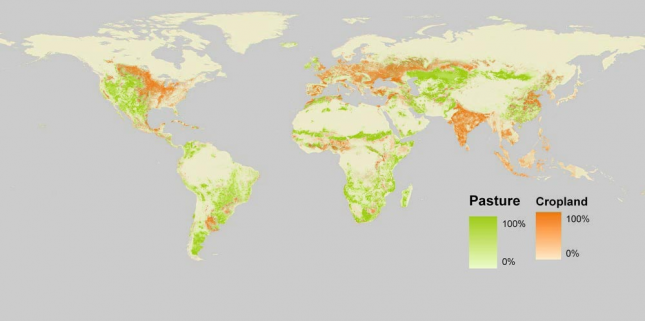

Roughly 37% of all land on Earth is being used for agriculture (Reference 1, Figure 1), and with population projected at 9 billion by 2050 and more people consuming a western-style meat-rich diet some studies expect food production will need to double (Ref 2). Part of the research I undertake concerns how human-induced land cover change influences climate, from in the distant past at the origin of farming thousands of years ago to potential future changes (Refs 3,4). The environmental impacts of farming are undoubtedly large and multifarious.

Figure 1. World Map of Cropland and Pastureland. Source: http://www.ourworldindata.org/data/food-agriculture/land-use-in-agriculture/

Greenhouse gas emissions from livestock farming are highlighted as particularly troubling in public science media (e.g. recent BBC Horizon episode “Should I eat meat? – how to feed the planet”, Ref 5) and scientific literature (Ref 6). Enteric fermentation in ruminants produces the largest proportion of methane of the whole agricultural sector (ahead of rice production). Nitrous oxide is also emitted from ruminants and in fertilizer production. In addition, carbon dioxide is emitted through fuel use. It has been estimated that 10-25% of total global greenhouse gas emissions are due to livestock agriculture (Refs 7, 8). Consequently, agriculture (especially livestock) is a major contributor to global warming.

However, greenhouse gas emissions are not the whole story. As land is deforested and modified to make way for crop or pasture land there are also biogeophysical changes that have immediate regional climatic impacts and may dominate the overall impact in the coming decades. Deforestation generally increases albedo (amount of incoming solar radiation that is reflected), which can result in cooling, especially at mid-latitudes. It also generally results in reduced evapotranspiration and lower moisture recycling, which tends to dominate the impacts towards the tropics. It is important to consider the potentially opposing biogeophysical impacts alongside the warming due to emissions of land use in setting climate change policy (Ref 3), not to mention other serious environmental problems associated with land use such as of desertification, overuse of freshwater, loss of biodiversity, and polluting nutrients (Ref 8).

One very recent study (Ref 6) suggests that it will only be possible to avoid further agricultural expansion and GHG emissions as well as provide global food security by 2050 with some degree of food ‘demand management’ and decreases in food waste (~9% of global carbon dioxide emissions come from producing food that is wasted). Converting to a less meat-rich diet has featured prominently in current media as a way to eat to be more climate-friendly. While the global picture seems simple, as concerned consumers it can be difficult to know what to eat to minimize our environmental impacts. Meat (especially beef and lamb) has the worst greenhouse gas emissions per kilogram produced, but when considered as emissions per calorie broccoli can be worse than chicken (beef and lamb still top the chart though). Consideration must also be made of food miles, water use, and other aspects of farming, such as whether grazing takes place on land that couldn’t be used for crops, or if there is a high risk of improper management leading to soil degradation. Getting all of the information, and acting appropriately, in order to make well-informed consumer choices is not straightforward. This is aside from the moral aspects of livestock farming practices, which are often in conflict with efficiency in production.

The implementation of ‘demand management’ based on climate mitigation is yet another issue. Recent surveys suggests that proposing people eat meat-free meals to reduce climate change can be a counterproductive message for those who are skeptical in the first place, and that motivation for dietary change would be better developed by combining multiple values of nature, health, and climate (Ref 9). A mainly vegetarian diet has been found to have positive effects on human health, such as lower levels of obesity, bowel cancer, and heart disease (Ref 10) in addition to reducing global greenhouse gas emissions and the need for agricultural land expansion. While there are substantial complications to reducing the environmental impacts of our food choices, if there are connections between our own health and the health of the planet then that seems like a good place to start making a change.

REFERENCES

1 http://en.worldstat.info/World/Land

2 Tilman, D., Balzer, C., Hill, J. & Befort, B. L. (2011). Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 1–5.

3 Davies-Barnard T., Valdes P.J., Singarayer J.S., and Jones C.D. (2014) Climatic Impacts of Land-Use Change due to Crop Yield Increases and a Universal Carbon Tax from a Scenario Model*. J. Climate, 27, 1413–1424.

4 Singarayer J.S., Ridgwell A.R., and Hetherington A. (2009). Assessing the benefits of crop albedo bio-geoengineering Environ. Res. Lett. 4 045110

5 http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04fhbrt

6 Bajželj, B., Richards, K. S., Allwood, J. M., Smith, P., Dennis, J. S., Curmi, E., & Gilligan, C. A. (2014). Importance of food-demand management for climate mitigation. Nature Climate Change.

7 Gill, M., Smith, P., Wilkinson, J.M. (2010). Mitigating climate change: the role of domestic livestock. Animal 4, 323-333.

8 Steinfeld, H., Gerber, P., Wassenaar, T., Castel, V., Rosales, M. and de Haan, C. (2006). Livestock’s long shadow: Environmental issues and options. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome, Italy.

9 de Boer, J., Schösler, H., & Boersema, J. J. (2013). Climate change and meat eating: An inconvenient couple?. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 33, 1-8.

10 Crowe, F. L., Appleby, P. N., Travis, R. C., & Key, T. J. (2013). Risk of hospitalization or death from ischemic heart disease among British vegetarians and nonvegetarians: results from the EPIC-Oxford cohort study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 97(3), 597-603.