By Jon Shonk

Thursday 25 September 2014

I am currently looking out of my office window at the Geophysical Institute at the University of Bergen (Figure 1), watching the rain fall steadily past the window from a grey sky. Dark rain clouds hang low, concealing the view of some of the seven mountains that surround the city.

I have been here for nearly two weeks now, collaborating with colleagues at the Institute. They tell me that this sort of weather is fairly standard for Bergen at this time of year. According to World Meteorological Organisation statistics, 2,250 millimetres of rain falls on Bergen on average each year – compare that with rainfall for London and Seattle, both often cited as rainy cities, at 557 mm and 950 mm respectively. Indeed, an internet search reveals many people claiming Bergen to be the wettest city in the world.

Figure 1. The City of Bergen, taken from the summit of Mount Ulriken. Photo: © Jon Shonk.

The reason why Bergen receives so much rainfall is its location. For a start, it is very close to the west coast of Norway and is surrounded by fjords, meaning that there is plenty of moisture about that may evaporate into the air. It is also surrounded by mountains, which can force this moist air to rise, causing clouds and rain to form. Its coastal position also puts it in the firing line for low-pressure systems that form over the North Atlantic and track eastwards.

But its high rainfall total is not Bergen’s greatest meteorological attraction – greater is the history of the Institute in which I am currently sitting, and the ground-breaking discoveries that were made here. The Geophysical Institute was founded in 1917 by a group of scientists that included Norwegian meteorologist Vilhelm Bjerknes. Prior to his time in Bergen, he built a set of mathematical equations to describe the evolution of the atmosphere – crucial equations that allowed the development of weather forecasting by computer many decades later.

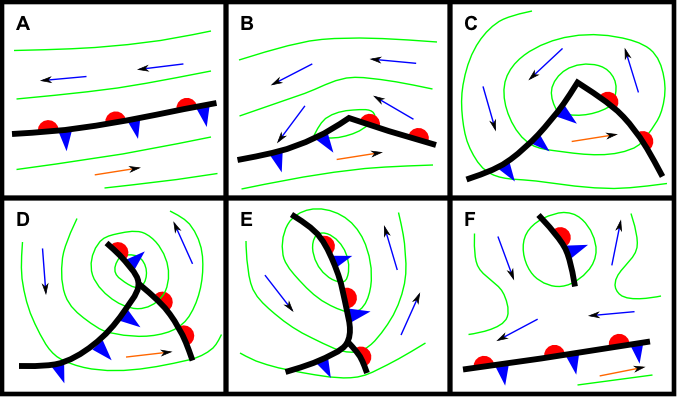

During the eight years Bjerknes spent working in Bergen, he made another great contribution to modern meteorology. Working with his son Jakob Bjerknes and collaborators including Tor Bergeron and Halvor Solberg, he came up with a simple model that describes the life-cycle of mid-latitude low-pressure systems. Perhaps the most impressive part of this feat is that, back in the early 1920s, there were no weather satellites, no rainfall radar and no computers to perform calculations – all they had was a network of weather observations from stations scattered across Norway. From these pieces of weather data, they deduced that low-pressure systems were organised structures, and that the bands of rain formed along locations where warm air and cold air meet. They are credited with introducing the term “weather front” to describe these regions, drawing inspiration from the trenches of the First World War. Their description of the life-cycle was so accurate that it has barely been modified since, living on in meteorological parlance as the Norwegian Model. Their original drawings of the evolution of a low-pressure system are still often recreated and appear in many textbooks and webpages (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The stages of evolution of a mid-latitude depression, based on the Norwegian model of cyclogenesis. Adapted from Bjerknes and Solberg, 1922.

Wish you were here!

Jon

Jon Shonk is the author of “Introducing Meteorology: a Guide to Weather”, published by Dunedin Academic Press.