As winter begins in Reading and snow already blankets the Alps, turn your thoughts for a moment to the southern hemisphere where extreme heat and bush fires are among the concerns of Australian forecasters at the beginning of summer.

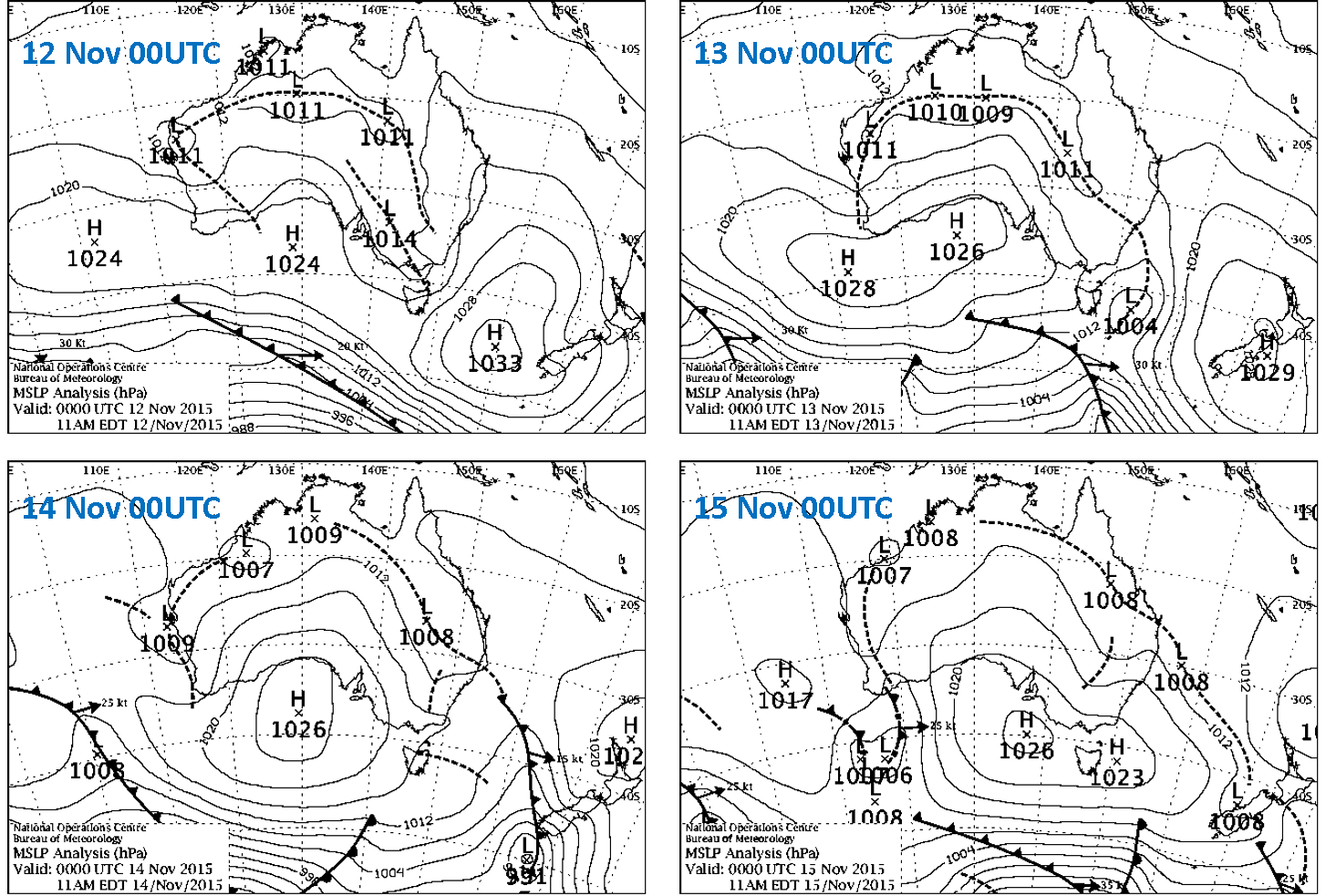

Perth in the south-west of Western Australia (WA) has an enviable Mediterranean climate. The majority of its 770 mm annual precipitation falls in the winter half-year (May-October), when the region is most influenced by mid-latitude westerly winds and the storm-track over the Southern Ocean (Figure 1). In spring the subtropical high pressure moves south as low pressure develops over Northern Australia ahead of the summer monsoon, leading to easterly winds bringing dry continental air to the south-west throughout the warm season. High daytime temperatures are usually mitigated by the development of a south-westerly coastal sea breeze – known locally as the Fremantle Doctor – that propagates over the coastal plain to the hills of the Darling Range further inland.

Figure 1. Climatological mean sea level pressure for Winter (JJA, left) and Summer (DJF, right).

However the climatological averages mask large variability, particularly in daytime temperature. There are periods when the sea breeze is weak, arrives late and fails to penetrate far inland, leading to very high afternoon temperatures. While the November climatological average Tmax is 25.9 °C, the record Tmax is 40.8 °C and temperatures above 35 °C are not uncommon. This year the temperature reached 39.2 °C on 14 November, its highest in November since 2010: exhausting conditions for the Second Test between Australia and New Zealand at the WACA, Perth’s cricket ground, and an excuse for even the Royal visitors to head for the beach.

This variability of the sea breeze is intimately linked to the Australian west coast trough, evident in the summer MSL pressure climatology shown above. Idealised modelling studies by Kepert and Smith (1993) and Spengler, Reed and Smith (2005) have shown that the trough is in essence a heat low in large-scale easterly flow, its position close to the west coast being determined by the surface heating contrast there.

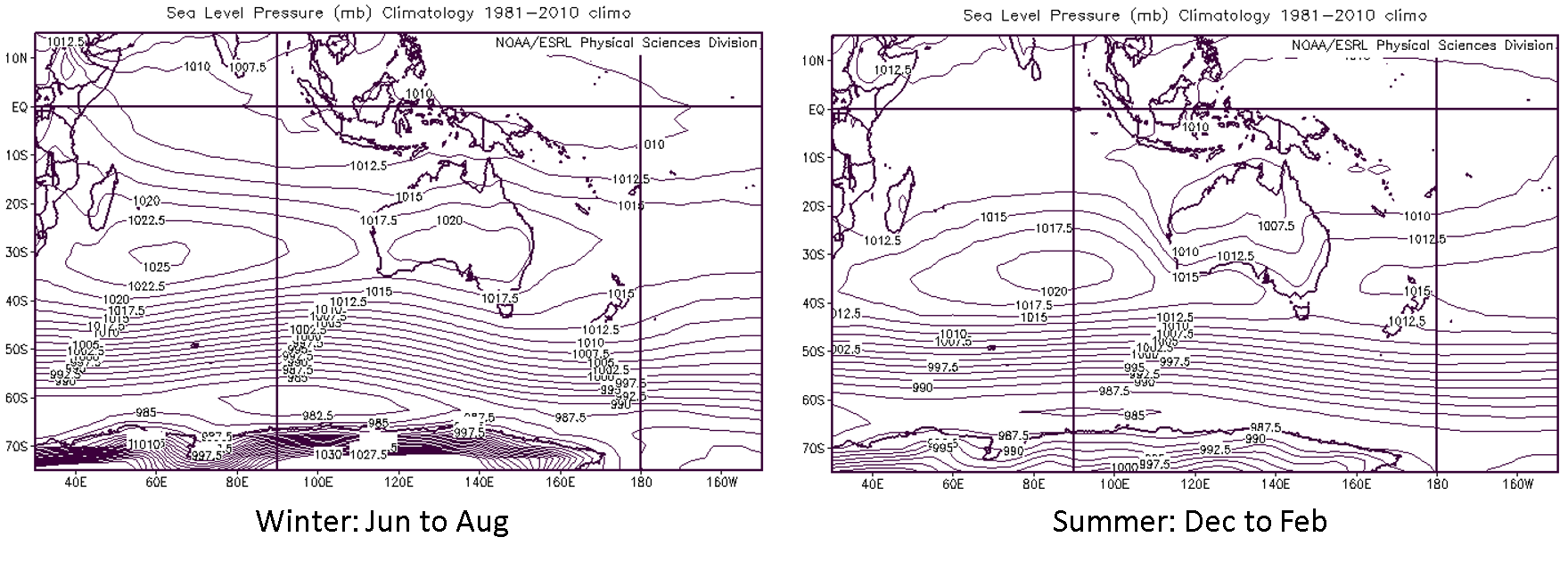

Heatwaves are associated with intensification of the trough, when the easterly low-level wind turns north-easterly and brings hotter air from the tropical continental interior to the south-west. Westward movement of the trough off the coast also inhibits propagation of the south-west sea breeze in the north-easterly large-scale flow and by increasing surface pressure over land relative to the ocean. This was the situation during the heatwave in mid-November this year (Figure 2).

Figure 2. PMSL sequence for Nov 2015, 12-15 quartet showing High in Bight propagating east during the mid-November heatwave 2015: Courtesy of the Australian Bureau of Meteorology.

In the warm season, south-west Australia is still influenced by eastward propagating upper level troughs and surface pressure anomalies equatorward of mid-latitude storms in the Southern Ocean. As the charts above show, these can modulate low-level meridional flow over the continent, tending to intensify the west-coast trough following the passage of high pressure and ahead of trailing cold fronts.

Intensification of the West Australian trough reduces static stability and increases low level convergence and lifting, leading to increased risk of severe convection. In the otherwise tinder-dry environment lightning readily initiates bush fires, putting life and property at risk in settlements bordering the natural bush. Sadly the mid-November heatwave that broke with spectacular night-time thunderstorms over Perth on 14th also led to an extensive wildfire that lasted a week and killed four people in Esperance on the south coast. The ubiquitous nature of these phenomena over millennia is evident in the evolution of the WA natural flora, which accommodates and even takes advantage of fire. Many species protect their seeds in hard insulating nuts that only open after heating, releasing seed in the post-fire period. In a continent that extends from the tropics to mid-latitudes, Australian forecasters have many hazards on their agenda, but risk of extreme heat and fire will only increase as average temperatures continue to rise.