By Ted Shepherd

Whenever an extreme weather or climate event occurs, scientists are invariably asked whether it can be blamed on anthropogenic climate change. The usual response from climate scientists has been that it is not possible to attribute the cause of specific events, because of the chaotic nature of weather and climate, but that the observed event may be an example of something that is expected to become more (or perhaps less) common because of climate change. In recent years, methods have been developed to try to provide a more concrete answer to this question, a subject known as “extreme event attribution”. However there is controversy about the methodologies, and published studies can draw apparently opposite conclusions about the same event – leading to confusion and the impression we scientists don’t know what we’re doing. It’s fair to say that extreme events have been exploited by both sides of the climate debate.

In response to this situation, the US National Academy of Sciences was asked to undertake a study on the science of extreme event attribution — the first of its kind. The report was developed over the last six months and released on 11 March. (Electronic copies are available for free download.)

(Full disclosure: I was on the author team for the report.)

One important set of conclusions and recommendations concerned the framing of event attribution studies. The question of whether climate change caused an extreme event is generally ill-posed, if cause is understood in the usual deterministic sense, because natural variability almost always plays a role — so there is a random element. An alternative question of whether climate change influenced an extreme event is also ill-posed; given that climate has changed, it is almost tautological that all events have been influenced to some degree by climate change. Yet that is often the question that studies address, with a yes or no answer provided; and it is certainly the question that the media normally ask. Instead, the relevant questions are: what was the influence, and how large was it? Even then, exactly how the question is formulated affects the answer. Examples of such questions are:

- Are events of this severity becoming more or less likely because of climate change?

- To what extent was the storm more or less intense because of climate change?

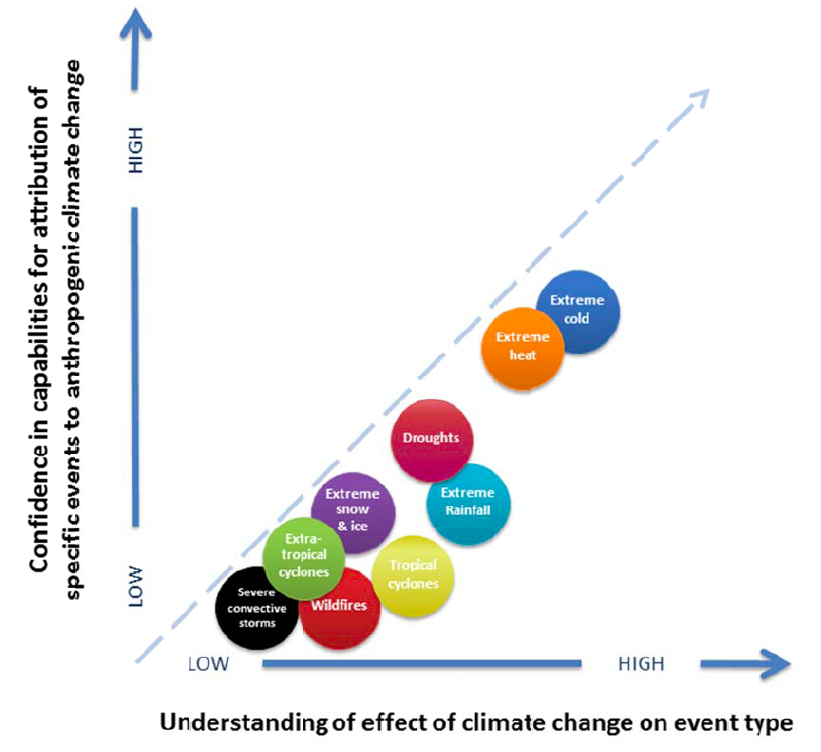

The take-home message from the report is that it is now possible to estimate the influence of climate change on some types of specific extreme events. Confidence is highest for extreme heat and cold events, followed by hydrological drought and heavy precipitation. There is little or no confidence in the attribution of severe convective storms and extratropical storms.

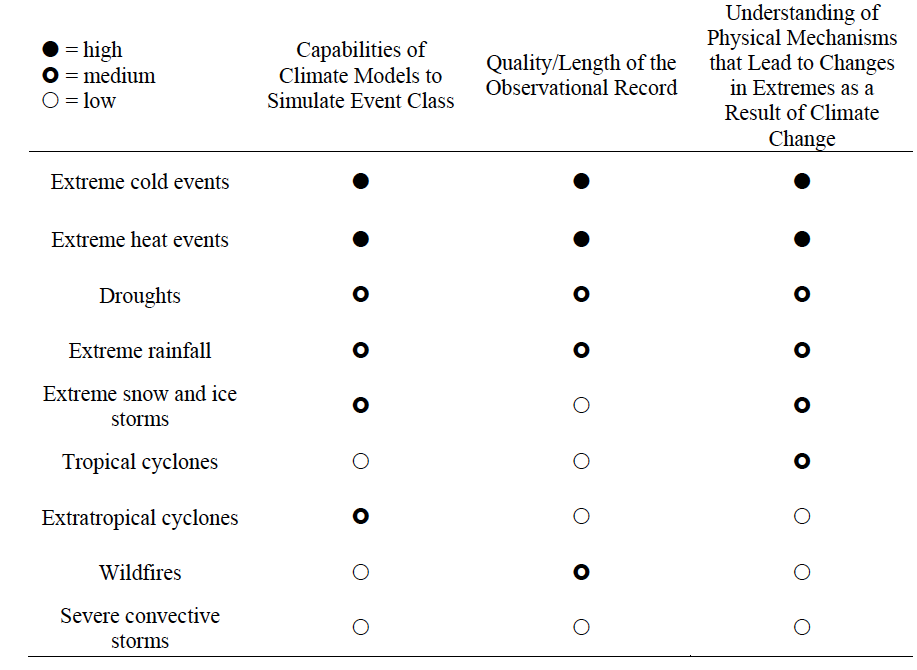

The overall summary, by extreme event type, is shown in Figure 1 in graphical form, with the basis for the assessment summarized in tabular form in Figure 2.

If you would like further background on extreme event attribution, at a less technical level, I can also recommend my recent review paper on the subject.

Figure 1. The committee’s assessment of overall confidence in capabilities for attribution of specific events, by event type, versus the understanding of the effect of climate change on that event type, in general. As overall understanding improves (horizontal axis), the potential for specific-event attribution increases (vertical axis). A position below the 1:1 line indicates the potential for improvement by technical means alone, but this potential is limited by the level of physical understanding. Source: National Academy of Sciences Attribution of Extreme Weather Events in the Context of Climate Change, March 2016.

Figure 2. The committee’s assessment of confidence in the ‘three legs of the stool’ needed for attribution of specific events: models, observations, and physical understanding. Source: National Academy of Sciences Attribution of Extreme Weather Events in the Context of Climate Change, March 2016.