By: Rebecca Emerton

Between September 2018 and May 2019, a record-breaking 15 tropical storms moved through the southern Indian Ocean. This marked the first season where two intense tropical cyclones, Idai and Kenneth*, made landfall in Mozambique, causing devastating flooding and affecting more than 3 million people, with over a thousand fatalities. As I write this, Cyclone Amphan, the strongest tropical cyclone on record in the Bay of Bengal, is heading towards the coast of India and Bangladesh, causing significant concerns due to extreme winds, rainfall and flooding from storm surge – all while also trying to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The anticipation and forecasting of natural hazards such as tropical cyclones and the flooding they cause, is crucial to preparing for their impacts. But it’s important to understand how well forecast models are able to predict these events, and the limitations of the forecasts – this information informs decision-making by national meteorological agencies, humanitarian organisations and the forecast-based financing community on how best to interpret forecasts of tropical cyclones. When should disaster management agencies trust a forecast for a landfalling tropical cyclone, and when should they not?

Satellite image of intense tropical cyclone Idai, 12th March 2019, overlaid with the ECMWF (European Weather Centre) forecasts of the tropical cyclone’s track towards central Mozambique.

Satellite image of intense tropical cyclone Idai, 12th March 2019, overlaid with the ECMWF (European Weather Centre) forecasts of the tropical cyclone’s track towards central Mozambique.

I’m currently working on a research project called PICSEA** (Predicting the Impacts of Cyclones in South-East Africa), which aims to provide insight into how well different forecast models are able to predict tropical cyclones and their associated hazards in the south-west Indian Ocean. In this blog post, I’ll talk about our visits to the national meteorological services we’re working with in south-east Africa, and highlight some of our key results so far, for how well we’re able to predict tropical cyclones in the region.

Working with national meteorological services in south-east Africa

We’re working with the Mozambique, Madagascar and Seychelles national meteorological services and the Red Cross Climate Centre on research that we hope will be of use to forecasters faced with providing warnings for tropical cyclones, and humanitarian organisations tasked with taking early action ahead of and during these events. In 2019, we were able to visit all three meteorological services, to meet the forecasters and researchers, to learn about their methods and learn from their local knowledge and experience. We were also able to discuss our research plans to gain their perspective and ideas on what questions were most important to tackle, and how best to collaborate on answering those questions.

Left: visiting the Limpopo River in Mozambique, discussing flooding from cyclones and spotting wild crocodiles. Right: at a cyclone discussion meeting at the Technical University of Mozambique (UDM) in Maputo, organised by the Universities of Reading, Bristol and Oxford, in collaboration with the national and regional hydrological services, the national meteorological and disaster management agencies, the Red Cross (Cruz Vermelha Moçambique) and UDM.

Left: visiting the Limpopo River in Mozambique, discussing flooding from cyclones and spotting wild crocodiles. Right: at a cyclone discussion meeting at the Technical University of Mozambique (UDM) in Maputo, organised by the Universities of Reading, Bristol and Oxford, in collaboration with the national and regional hydrological services, the national meteorological and disaster management agencies, the Red Cross (Cruz Vermelha Moçambique) and UDM.

I came away from these visits with a much better understanding of the procedures around forecasting tropical cyclones in each country and the challenges faced (ranging from which forecasts to trust, to communicating forecasts and warnings in areas where many different local languages are spoken), alongside some great ideas for our research – which models to focus on, which questions would be the most useful to answer (and which would be less useful!), and how best to communicate and visualise our results. A further trip to Mozambique also gave us the opportunity to meet with representatives from the national meteorological, hydrological and disaster management institutes, the Red Cross, and academics from the Technical University of Mozambique, to discuss experiences of forecasting and responding to Cyclones Idai and Kenneth, and furthering the collaborations between the various national and international organisations. I also took a little time off to explore a part of the world I’ve been wanting to visit for a very long time!

Taking some time off to go hiking in the Seychelles (top left) and explore Madagascar’s rainforests, mountains, deserts and beaches, spotting lemurs (top right & bottom left) and baobabs (bottom right).

Taking some time off to go hiking in the Seychelles (top left) and explore Madagascar’s rainforests, mountains, deserts and beaches, spotting lemurs (top right & bottom left) and baobabs (bottom right).

What does the research show?

Our research has focussed on evaluating how well the UK Met Office and European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ensemble and high-resolution deterministic models are able to predict tropical cyclones in the south-west Indian Ocean. We’re looking into how closely the models are able to predict the path the tropical cyclones will take, the amount of rain they’ll produce, and whether the models correctly capture the strength of the tropical cyclones. In the next couple of paragraphs, I’ll briefly discuss some highlights from our results for the UK Met Office forecasts (while we continue to process data for ECMWF!).

We’ve been looking at forecasts of tropical cyclones over the past 10 years, and we’ve seen significant improvements in the accuracy of the forecasts over that time, for both the path/track of the storms, and also the intensity/strength. We know that forecast models in general can often struggle to predict the intensity of tropical cyclones, typically under-estimating their strength, but it’s encouraging to see significant improvements in the forecasts of pressure and wind speed as the models are upgraded.

Change in track error over the past 10 years, for an example predicted storm. If, 3 days in advance, you were to predict a tropical cyclone to be in the centre of the circle, then based on the typical errors across many forecasts, the actual position of the storm in 3 days’ time could end up being anywhere within the blue circles. The left map shows the UK Met Office deterministic forecast model from 10+ years ago (July 2006 – March 2010), the right map shows the current version of the model (running since July 2017). The dark shaded circle indicates the average track error, and the lighter circle indicates the error for the worst forecast of any storm using that model.

Change in track error over the past 10 years, for an example predicted storm. If, 3 days in advance, you were to predict a tropical cyclone to be in the centre of the circle, then based on the typical errors across many forecasts, the actual position of the storm in 3 days’ time could end up being anywhere within the blue circles. The left map shows the UK Met Office deterministic forecast model from 10+ years ago (July 2006 – March 2010), the right map shows the current version of the model (running since July 2017). The dark shaded circle indicates the average track error, and the lighter circle indicates the error for the worst forecast of any storm using that model.

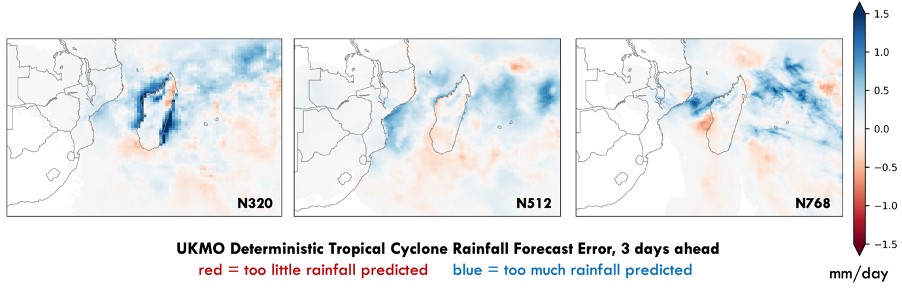

Errors in UK Met Office deterministic forecasts of tropical cyclone rainfall, in three different versions of the model from N320 (July 2006 – March 2010), N512 (March 2010 – July 2014) and N768 (July 2014 – July 2017). Significant over-estimations of the rainfall around Madagascar in the N320 version of the model are improved in later versions of the model, but results vary by region, with the forecasts predicting too much rainfall in some areas, too little in other areas.

Errors in UK Met Office deterministic forecasts of tropical cyclone rainfall, in three different versions of the model from N320 (July 2006 – March 2010), N512 (March 2010 – July 2014) and N768 (July 2014 – July 2017). Significant over-estimations of the rainfall around Madagascar in the N320 version of the model are improved in later versions of the model, but results vary by region, with the forecasts predicting too much rainfall in some areas, too little in other areas.

We’ve also been looking into whether certain background tropical conditions impact the accuracy of tropical cyclone forecasts. We’ve found that there are certain phases of the Madden-Julian Oscillation (which is the eastward movement of a large region of enhanced and suppressed tropical convection, and the different phases describe the location) during which forecasts of tropical cyclone intensity are improved (phases 1 and 2 for forecasts up to 4 days ahead) compared to other phases. With further research, we hope to identify other such potential ‘windows of opportunity’ for more accurate forecasts, and also highlight times when forecasts may be less accurate than usual – information that is also key for forecasters and decision-makers.

What’s next?

While there’s always plenty more research to be done, we also plan to work with the Red Cross Climate Centre and our project partners in Mozambique, Madagascar and the Seychelles, to produce forecast guidance documents and infographics. These could be used to communicate the outcomes of the research alongside other key information, in a way that can be used by the forecasters who are monitoring, predicting and providing warnings for tropical cyclones in the region. As well as looking at forecast models, national meteorological services also receive regional forecasts and warning bulletins for tropical cyclones from the Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre, which for the south-west Indian Ocean is Météo-France in La Réunion.

While the current pandemic situation may have sadly changed our plans to host visiting scientists here at the University of Reading for two months to work together on this (we had the pleasure of working with Hezron Andang’o and Lelo Tayob from the Seychelles and Mozambique meteorological services before their time in Reading was cut short back in March), I look forward to continuing our work remotely with all of our partners for now, and hopefully to visiting each weather service again in the future!

* Read more about the forecasts and response to Cyclones Idai and Kenneth in this presentation and keep an eye out for our upcoming paper:

Emerton, R., Cloke, H., Ficchi, A., Hawker, L., de Wit, S., Speight, L., Prudhomme, C., Rundell, P., West, R., Neal, J., Cuna, J., Harrigan, S., Titley, H., Magnusson, L., Pappenberger, F., Klingaman, N. and Stephens, E., 2020: Emergency flood bulletins for Cyclones Idai and Kenneth: the use of global flood forecasts for international humanitarian preparedness and response, under review

**PICSEA is a SHEAR Catalyst project funded by NERC and DFID, led by Nick Klingaman with Kevin Hodges, Pier Luigi Vidale and Liz Stephens, and international project partners Mussa Mustafa (INAM, Mozambique), Zo Rakotamavo (Météo Madagascar), Vincent Amelie (SMA, Seychelles) and Erin Coughlan de Perez (Red Cross Climate Centre). Oh, and I do the data analysis!